The Reparations Loan is Dead

Long live the reparations loan

On the 18th, the European Commission finally met for the climactic moment of the reparations loan saga. At stake were Ukraine’s war effort, the future of the European banking system, the sovereignty of EU member states, and €210 billion in frozen Russian cash. “No one will leave the EU summit until a solution on financing Ukraine is found,” said EC president Ursula von der Leyen that morning. Von der Leyen was serious, as European leaders spent a marathon session attempting to hash out a solution to the seemingly insurmountable obstacles that had thus far prevented the reparations loan scheme from becoming a reality. A last-minute attempt to satisfy the Belgians with an “uncapped” EU backstop for their potential liability was rejected as leaders realized they’d potentially face a bailout of the entire Belgian banking system. Late that night, diplomats involved in the negotiations reported that the scheme was finally dead. Ukraine will instead be provided with €90 billion raised through joint EU debt from capital markets. The British plan to use the frozen Russian assets stored in their banks failed simultaneously.

With the full collapse of the scheme, diplomats are speaking more freely, and we have confirmation of Belgian prime minister Bart de Wever’s hint that other EU states were “hiding” behind him, or in other words, quietly supporting him. The full coalition contains, of course, Belgium and Russia-neutral renegades Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic. Banking microstates Luxembourg and Malta were on Wever’s side, along with Ukraine-skeptical Italy and Bulgaria. The most significant revelation of the past few days is that Emmanuel Macron’s France played a significant role in torpedoing a last-minute attempt to make a deal whereby the EU would agree to bail the Belgians out for the entire amount of the Russian assets if things went south.

Readers of our reporting on this were likely unsurprised by the EC’s failure to find a path forward for the reparations loan. But the last-minute decision to take on new debt to fund Ukraine happened despite there having been just as many obstacles to doing so as there were to the reparations loan. Von der Leyen, Merz, and their allies had to make major compromises to overcome the roadblocks.

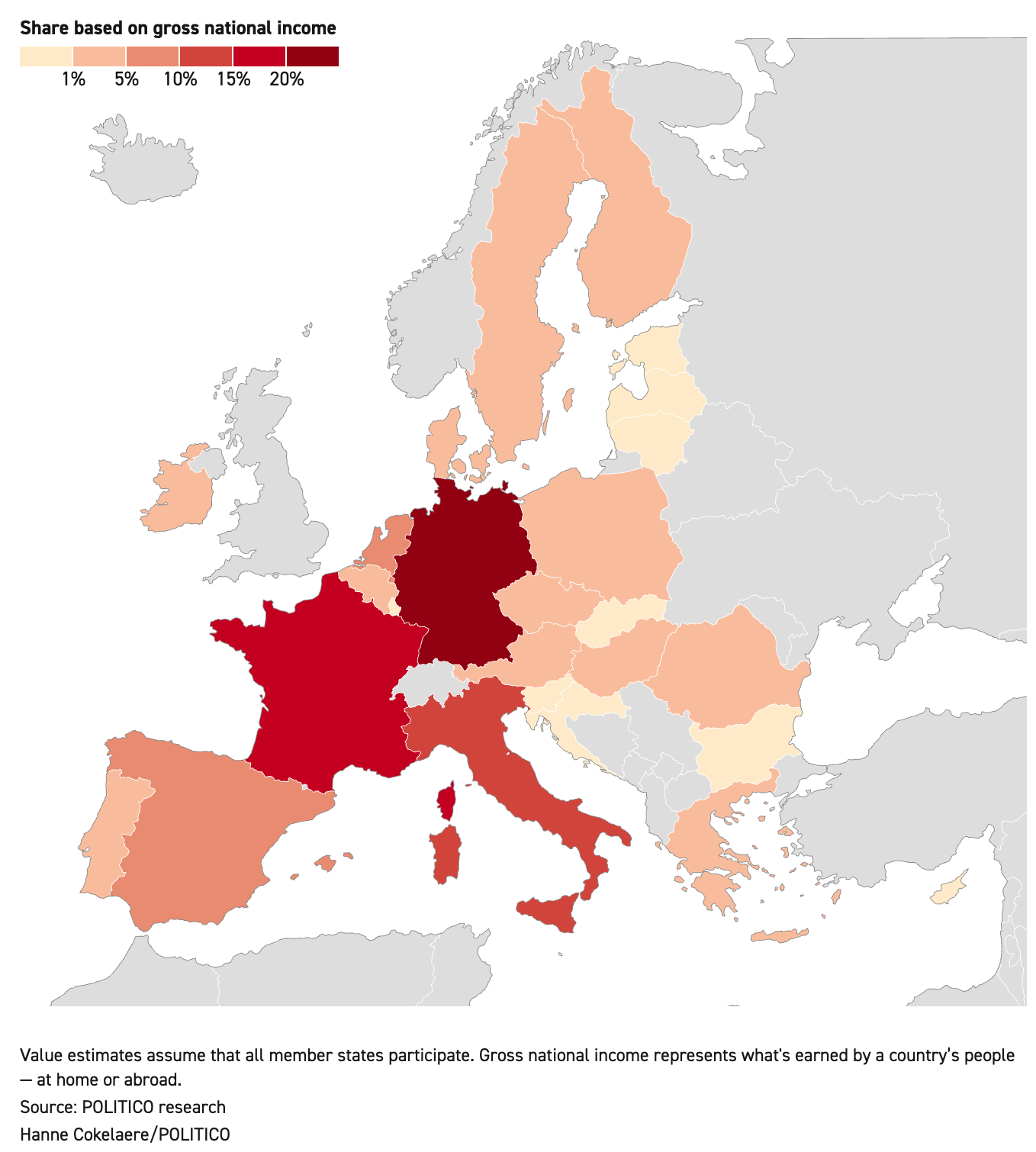

The first compromise is notable more as a moral defeat than a practical one. Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia were sure to veto the joint borrowing plan, which would have forced the EC to again activate controversial emergency powers for the second time in a month to force the scheme through with a simple majority. Doing so would have opened von der Leyen’s coalition up to legal challenges and the increasing perception that the EU’s democratic mechanisms, or what remains of them, are fully broken. To avoid this, the terms of the agreement exempt the trio of countries from any liability stemming from the new debt, meaning they won’t have to help make the EU whole if the Ukrainians fail to repay the loan. While this does damage to the image of EU unity, these three countries would have been responsible for perhaps 4% of any such liability, or a few billion euros. This risk will be spread to the remaining member states. For Orbán, Fico, and Babiš, it’s around a billion euros they can assure their taxpayers they won’t be on the hook for.

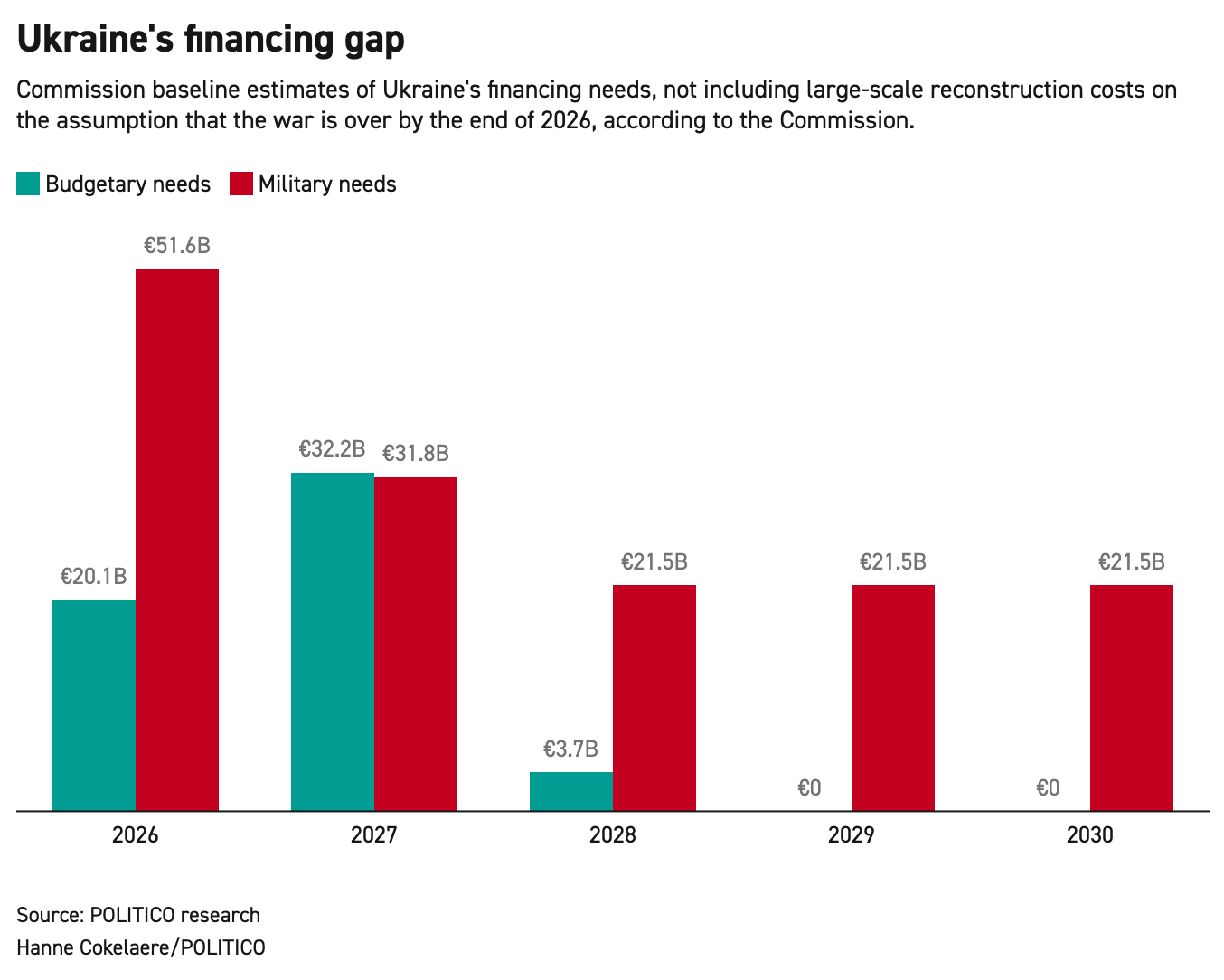

The second compromise is more consequential: the loan to Ukraine will provide only €90 billion over the next two years. €45 billion a year is just half of what the Ukrainians received in combined US/European aid each year from 2022 to 2024, and the war has gotten significantly more expensive since then. We can take the EU’s own projections as evidence of this, because they made detailed calculations when prospectively divvying up the €210 billion in Russian assets:

This chart, which was posted by Politico just two weeks ago based on EC numbers, assumes the war will end in 2026, only covers financing needs (what the Ukrainians can’t pay for themselves), and doesn’t include reconstruction costs, which the World Bank estimates will exceed €500 billion. If the Ukrainians have a €72 billion budgetary hole just for 2026, €45 billion certainly won’t cut it, even factoring in the few billion the IMF and Germany have pledged. As we’ve covered previously, even the €165 billion reparations loan wouldn’t have been enough to cover the Ukrainians for much longer than a year or two. Last month, the Economist calculated the Ukrainians would need a staggering $389 billion (€332B) in external financing over the next four years. The reality is that the Ukrainians need both massive loans from the EU and the Russian assets. Without the latter, they’ll have no choice but to make cuts. If we consider military costs, budgetary deficits, the cost of reconstruction, and Ukraine’s existing external debt, the country likely needs over a trillion euros of financial assistance over the next five to ten years.

Although this has been mostly overlooked amidst all the complexity of the reparations loan, the EU is apparently letting go of another major item with this compromise. With the Russian assets totaling €210 billion and the reparations loan plan only giving the Ukrainians €165 billion, what would have happened to the other €45 billion? The Europeans intended to use it to pay themselves back for a loan the G7 issued to the Ukrainians in 2024. The interest on this loan is currently being paid from the profits taken from the frozen Russian assets. Since this loan will now go unpaid, those profits can’t be used to pay the interest on the new one, and European taxpayers will be on the hook for €3 billion a year.

Adding these two loans to Ukraine’s other existing debt obligations, Ukrainian external debt has exploded to $298 billion. This will skyrocket the Ukrainians to fourth place worldwide in debt-to-GDP ratio (assuming Ukraine’s GDP can even meaningfully be calculated), at 155%. The Europeans will hold more than half of this debt while being significantly exposed to international lending institutions like the IMF that hold much of the remainder. If the Ukrainians are unable to pay, the EU has no plan in place to cover the over €130 billion liability other than the European taxpayer.

And the loan will have strings attached. The terms of the loan will require continued Ukrainian deference to Western-controlled anti-corruption organs like NABU. And as we’ve covered in the past, European aid to Ukraine won’t do the Europeans much good if their money is funneled to the US for weapons. Although the Ukrainians have repeatedly denounced the idea, the loan will require its money marked for military assistance to be spent on EU-produced weapons, unless the EU produces no viable option for a given need. The Ukrainians have been so resistant to this idea because it greatly limits the quantities and types of weapons they can purchase. With EU states like Italy dropping out of NATO’s PURL program to buy US weapons for Ukraine, procurement options for the AFU are rapidly dwindling.

To mitigate the perceived financial burden, the EU has declared that the immobilized Russian assets—which are now frozen indefinitely thanks to the activation of emergency EU powers—will not be released until the Russians pay Ukraine reparations. But this amounts to little more than a loose promise. Because the assets still reside in Euroclear accounts, their immobilization remains sensitive to legal challenges both from the Russians themselves and to the Article 122 invocation. And because the Europeans have no Russian pool of cash to backstop the loan, it’s an effective admission that the EU itself won’t be getting paid back anytime soon, or perhaps ever.

The Western commentariat has had a gloomy reaction to the failure of the reparations loan scheme. The Wall Street Journal’s editorial board called the loan “another half-measure.” A piece in Politico today went further, singling out the failure to pass the reparations loan scheme as an EU defeat that will lead directly to the end of the war in 2026 and an unfavorable peace for Ukraine. The piece cites falling European public support for Ukraine funding (45% of Germans want to cut aid) as a key danger in building support for the future loans Ukraine will need. The Financial Times linked the failure to a deepening rift between Macron and German chancellor Friedrich Merz, while also citing equally concerning divisions around a contentious trade deal that fractured along similar lines. Brookings Institution fanatic Robin Brooks was furious, calling it “a dark day for Europe” and a “disaster.”

As responsibility for the war falls solely on Europe’s shoulders, Ukraine’s future is an open question. If this is the best the EU can muster despite all the pressure and politicking, who will pay to rebuild Ukraine when the war is over? Can the EU reasonably expect to keep the war going with half the aid it’s been receiving? And most disturbingly (or it should be, for the EU), who will cough up the hundreds of billions more Ukraine will require over the ensuing years?

Russian attritional warfare not only attrites men (Ukrainian), materiality (NATO's and the West in general) and will (both Ukraine's and the West), but also the building blocks of all these things - being money. The idea of attrition is that it builds pressure until the enemy implodes or becomes dysfunctional. The financing of Ukraine debate in the EU shows it is becoming increasingly dysfunctional.

Incredible breakdown of how the reparations loan collapsed under its own contradictions. The part about France quietly torpedoing the Belgian bailout is huge but kinda buried in all the technical details. What I found most striking is the debt-to-GDP math showing Ukraine at 155%, which puts them in Greece 2015 territory except Greece had functioning tax revenue and wasn't actively fighting a war. The €90 billion being half of previous aid levels while costs escalate seems like they're just delaying the inevitable reconing.