On Russian Strikes Targeting Ukrainian Gas Infrastructure

Will Ukraine be able to keep the heat on?

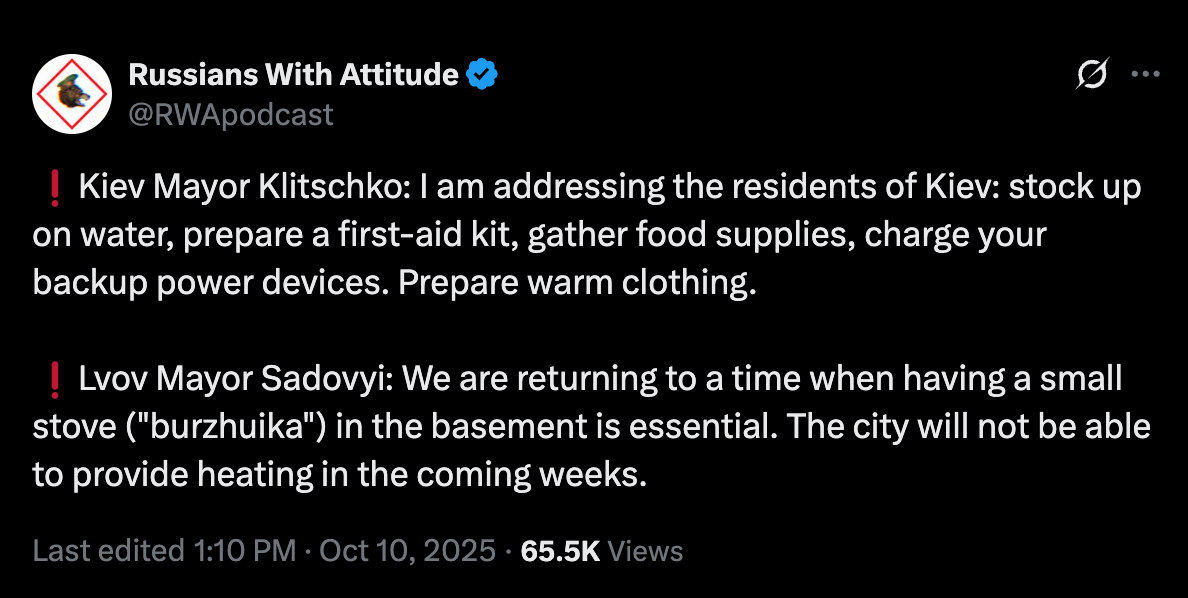

Over the past week, Russian forces have massively increased their missile campaign against Ukrainian energy infrastructure. A strike on October 3rd targeted gas production facilities in Poltava and Kharkov with 35 missiles and at least 60 long-range drones. Bloomberg reported that the damage to these two sites has brought around 60% of the country’s gas production offline. The Ukrainians are planning to increase their gas imports over the winter by 30% to compensate, importing at least 4.4 billion cubic meters over the season, equivalent to $2.2 billion, or 20% of the country’s typical annual consumption. This figure is likely to rise.

So where does this leave Ukraine, especially if Russian strikes continue? Ukraine relies on gas principally for heating. The share of gas used for residential homes, larger district-level heating stations, and industrial/commercial use is roughly equal. 78% of Ukrainian households depend on gas as their primary heat source. Industrial concerns use between 1 bcm (billion cubic meters) and 6 bcm of gas a quarter depending on the season, and 11% of Ukraine’s electricity generation comes from gas power plants. Ukraine’s total gas consumption is around 20 bcm annually.

The Ukrainian government projects that it will import 5.8 bcm of pipeline gas this year, more than twice what it imported pre-war, despite massive reductions in population and falling consumption. Around half of this gas transits through Hungary, with another quarter of the total through Poland, an additional quarter through Slovakia, and insignificant amounts through Romania and Moldova. These pipelines once carried Russian gas through Ukraine to Europe, generating billions in transit fees for the Ukrainians, but this agreement fully terminated at the beginning of this year. Since then, these pipelines operate in “reverse flow," sending gas backwards through mostly Soviet-era infrastructure to Ukraine.

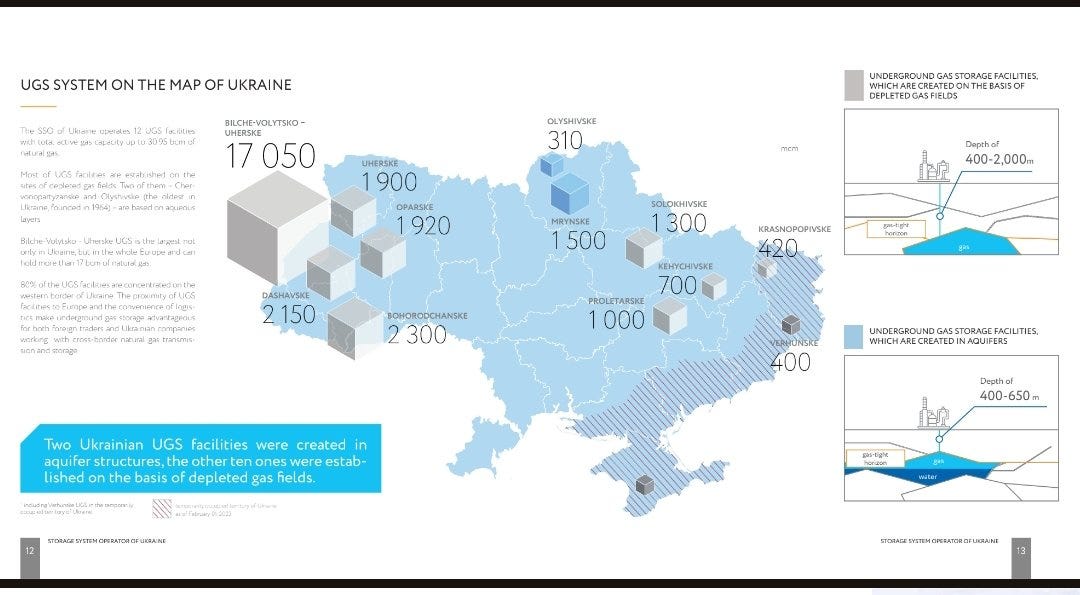

While the transit agreement was in effect, the Ukrainians were able to take advantage of a complex scheme whereby they imported Russian gas from Gazprom while simultaneously “buying” it from EU sellers without it ever physically moving gas through the seller’s infrastructure. This allowed them to save significantly on transportation fees. With the transit agreement now terminated, Ukraine is no longer strategically placed between Russia and its former customers in the EU, making Ukraine’s gas storage facilities (the largest in Europe) inconvenient to access. The only way to fill these facilities for EU countries is now an expensive round trip from central Europe to Ukraine and back again, with corresponding transit fees, making Ukraine an economically infeasible option for EU gas storage. With a restoration of Russian relations with the EU looking increasingly unlikely, and the Ukrainians refusing to allow the transit of Russian gas through their territory, the Ukrainian gas network has gone from a central node in a vast Eurasian web to a distant peripheral spur. Its infrastructure serves little purpose now besides meeting its own modest, domestic needs.

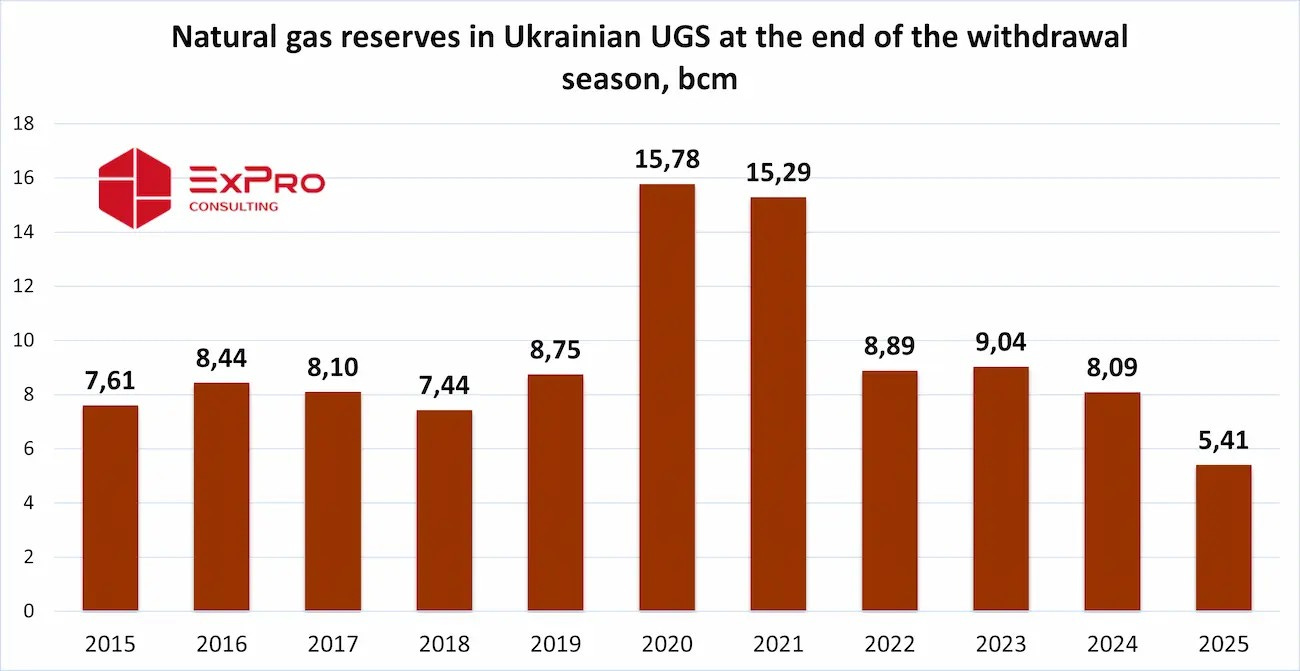

Ukrainian gas storage facilities have a total capacity of 30 bcm, but only a third of this capacity is currently being utilized after European companies began to pull their stocks out of the country amidst increasing Russian attacks. The Ukrainians have approximately 11 bcm available, but 4.7 bcm of this gas is in strategic reserves which are more difficult and expensive to access. Altogether, this amount is 20% less than the government’s target for the winter, which the Ukrainian gas industry also failed to meet in 2024, despite imports and domestic production. This resulted in the country being brought to the brink of a “gas blackout,” with stocks just barely allowing the Ukrainians to scrape by.

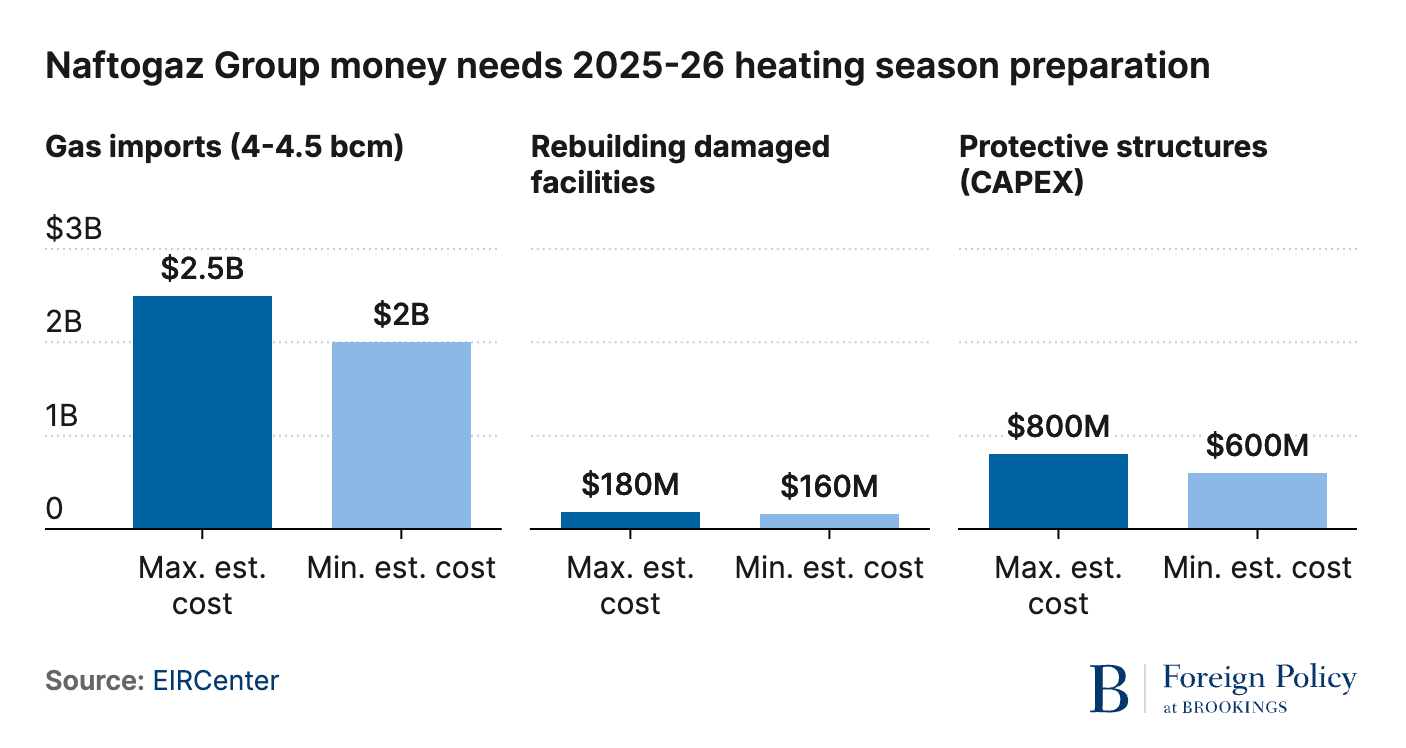

The latest Russian strikes have brought this issue to a head, because those estimates assume typical domestic production. Unless the Ukrainians can bring the damaged infrastructure back online quickly – and this may not be possible – they may not be able to provide reliable heating through the season. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development will be instrumental in providing funding for both imported gas and the equipment and materials needed to repair the damage. The EBRD has “invested” billions into Ukrainian energy infrastructure since the war began, handing money over to Ukrainian state enterprises like Naftogaz in the form of loans guaranteed by the EU under the Ukraine Investment Framework.

Yesterday the EBRD announced an emergency financing deal in response to the October 3rd attack, but this program will need to be put into place with unprecedented speed. It comes on the heels of another €500 million loan for gas purchases in August, also classified as an “emergency.” Attempting to fill Ukraine’s reserves now, as extraction season begins, will cost Ukraine (or, realistically, the EU) almost twice what it would in the summer. Repairing the damage caused by Russian strikes this year is an additional hurdle. At least $180 million in funding is required to repair the damage that has already been done earlier this year. Total needed repairs to the Ukrainian grid are estimated to cost at least $878 million. Gas infrastructure components are highly specialized and not mass produced.

Ukrainian gas reserves at the end of “withdrawal season,” which runs from November to April, have been declining since the war began, and fell to a third of their 2021 high last season. In January, reserves dropped dangerously to 3.4 bcm (less than 20 days of winter consumption). The 5.4 bcm remaining in April of 2025 cut things far too close for comfort, as an interruption of gas transit to strategic storage sites could leave parts of the country cut off, without enough local supply to keep the heat on. This amount represents significantly less than a single quarter of winter gas consumption, and there are hard limits on how much gas Ukraine can produce domestically and import from the EU during injection season. Presuming a maximum throughput of 60 mcm of gas a day and an infinite supply of money from EU loans, Ukraine can import less than 1 bcm a month for storage after accounting for consumption needs. This means the pipelines would need to be running at maximum capacity around the clock to refill the reserves enough to be ready for the withdrawal season next year, assuming domestic production were cut off.

The good news for Ukraine is that its domestic production has yet to be entirely destroyed. But with the termination of the transit deal, and increasing Ukrainian strikes on Russian oil infrastructure, the Russians have shifted their strategic focus, apparently feeling they no longer have any reason to hold back on striking Ukrainian gas infrastructure. In August, they destroyed a key pumping station servicing the Transbalkan route through Odessa, planned to provide Ukraine with US and Azerbaijani LNG.

The vast majority of Ukraine’s gas storage capacity is secured in underground gas storage (UGS) systems within depleted gas wells or underground aquifers that lie hundreds to thousands of meters underground. The gas in these reservoirs is as inherently safe from attack as any strategic resource could conceivably be. More than half of Ukraine’s gas storage capacity lies under the Bilche-Volytsko-Uherske site in Lvov oblast. While the gas deep beneath this site may be safe, the infrastructure on the surface needed to extract it is not. The Russians have struck BVU twice: once in 2024 – likely to dissuade EU providers from storing gas in Ukraine – and once in January this year, two weeks after the termination of the transit deal.

Massively increased Russian long range drone production rates mean that keeping sites like BVU offline permanently is now a possibility. And if the Ukrainians have to rely even more heavily on imported gas, a shortage of storage capacity will result in service interruptions as storage is still necessary to provide a buffer for demand volatility over the course of the day, or during cold snaps.

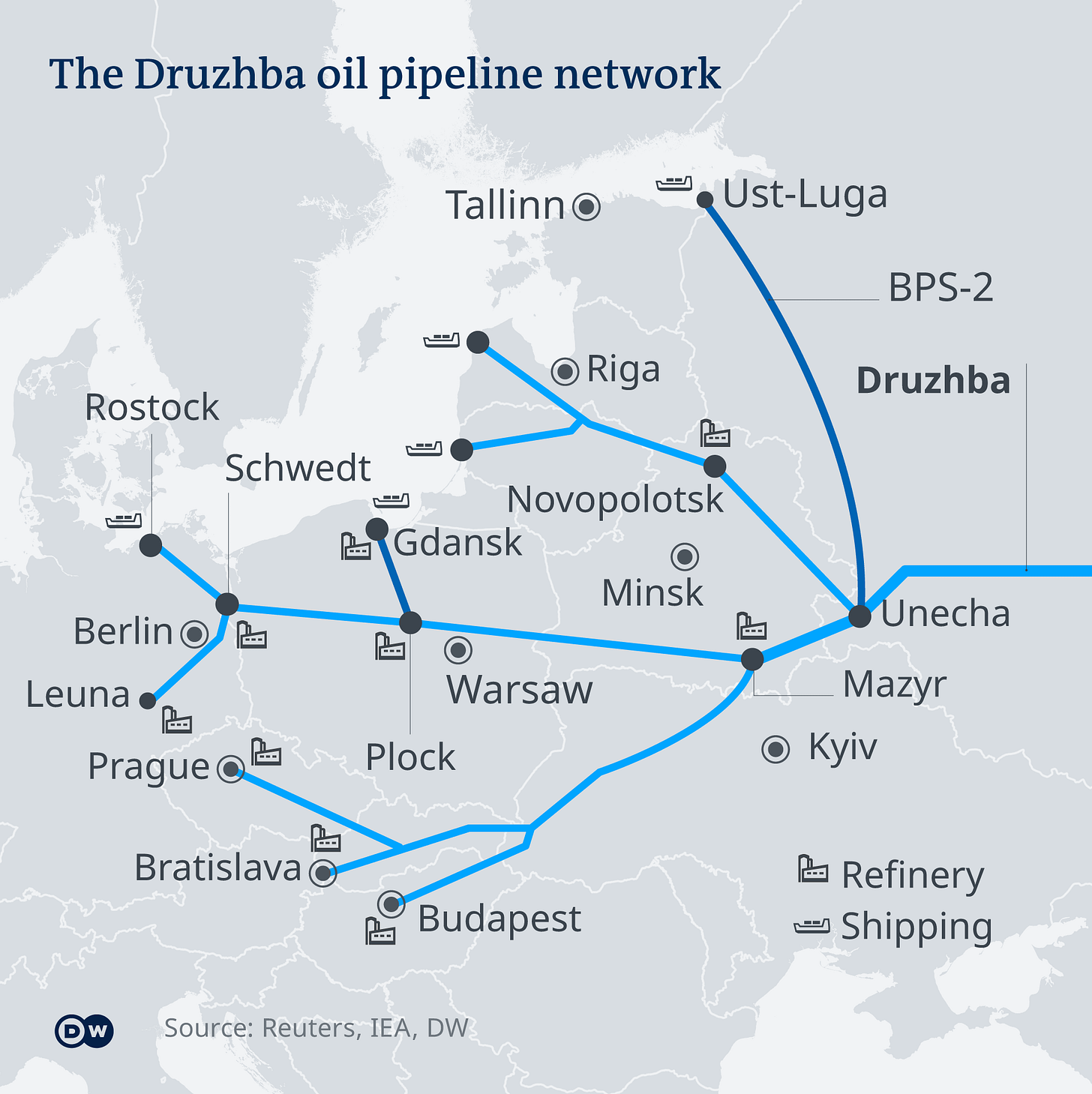

Potentially just as damaging would be strikes on the pipeline infrastructure Ukraine depends on to import gas from the EU. Russia has entirely refrained from targeting these pipelines, but in August, the Ukrainians broke the taboo on attacking EU connected pipelines (not counting Nord Stream) by striking pumping stations of the Druzhba oil pipeline in Bryansk, halting flows to Hungary and Slovakia. There is likely a complex game being played with the tenuous relationship between Hungary, Russia, and Ukraine. Ukraine depends on Hungary for half its gas, but Hungary has refused to divest itself of its dependence on Russian energy imports. If the situation continues to escalate, Ukraine can threaten to cut Hungary off from Russian oil transiting through Ukraine, but Hungary can in turn threaten to cut Ukraine off from its own gas exports. Similarly, Russia could target Ukrainian gas pipeline turbine stations, cutting Ukraine off from Hungary and devastating Ukrainian import ability, but only at the cost of cutting into the revenues of a “friendly country.”

If, however, the situation remains stable and Russian strikes on Ukrainian gas infrastructure cease, the Ukrainians are likely to make it through the winter, albeit with some rationing. The apparent key factor is Russian strategic thinking. Their missile campaign has reached unprecedented intensity over the last two weeks, but it’s not clear if this is a tit-for-tat response to Ukrainian attacks on Russian petroleum resources, or a permanent decision to destroy the Ukrainian energy system. If it’s the latter, there are several options on the table to impose a crisis on the Ukrainians.

Thanks to burrrson and Kinez on X for contributing to this piece

It’s the latter. Russia tried last winter, but didn’t quite have the numbers to succeed.

Now we’re seeing daily strikes of hundreds of Gerans, so the tools are there.

And since Zelensky has shown no willingness for peace negotiations, any incentive to hold back is gone.

I think the Russians have decided to try and de-energize Ukraine as much as possible this winter to incapacitate the Ukrainian government and society (and by proxy the AFU) as much as possible. The failure of the meeting in Alaska to provide any sort of diplomatic resolution to this conflict was probably the last straw for the Russians imo and I don’t think they want this war to drag on into 2027.