Deadlock in Brussels on Funding for Ukraine

No progress on the "reparations loan"

The European Commission and Belgian leadership met in Brussels on the 7th of this month in an attempt to resolve the impasse on issuing the controversial “reparations loan” backed by frozen Russian assets to Ukraine. After failing to reach a consensus in October, the EU committed to “exploring alternative proposals” through December, but the Belgians remain unconvinced by said exploration:

“For Belgium, it is essential that all options are explored. Every possible approach must be examined with rigour and transparency, to ensure the best solution. To be frank, we are still waiting for the other options that the European Commission was meant to present, as agreed at the European Council in October.” - EU source (Euronews)

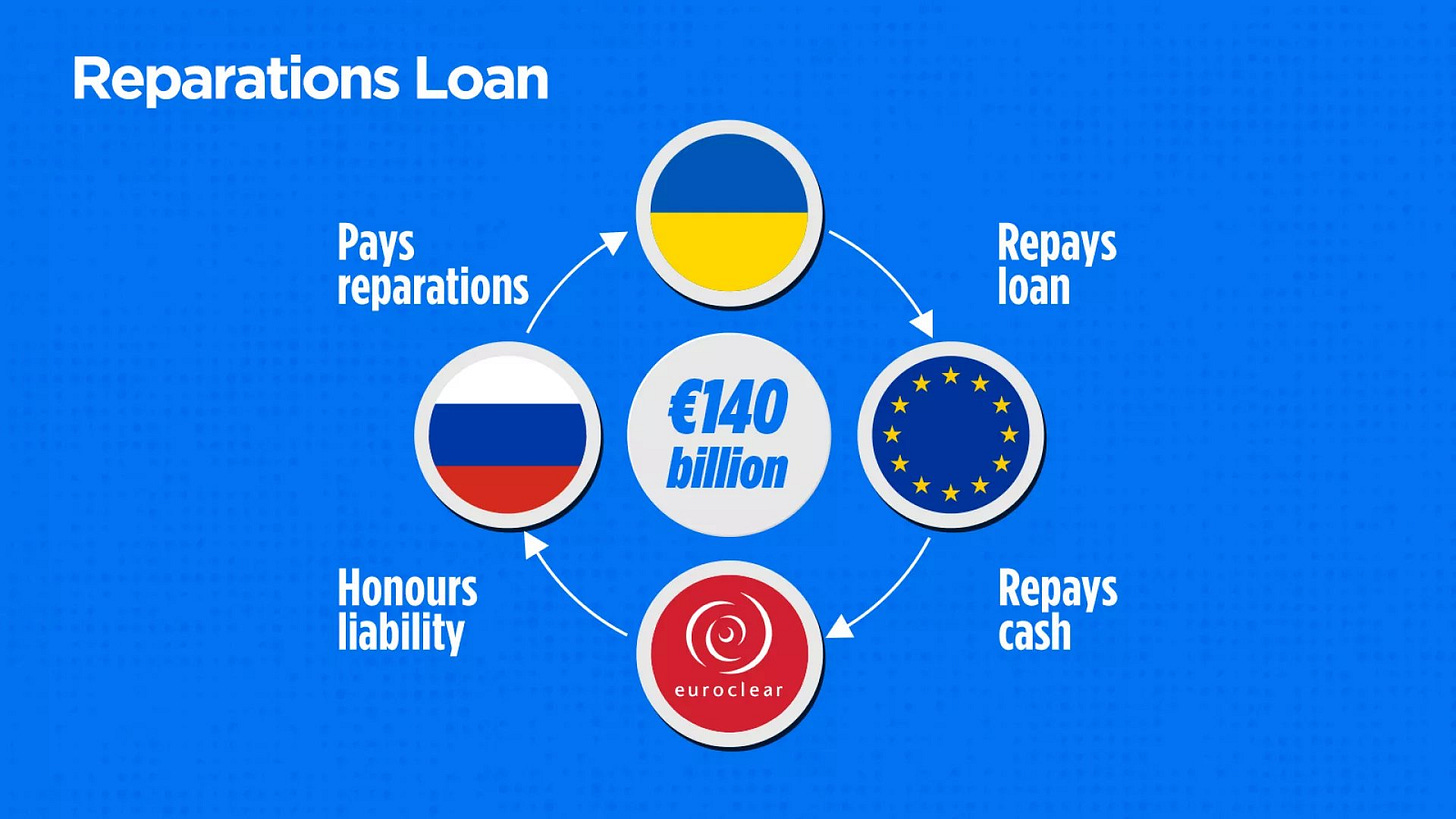

This is all quite difficult to parse for the average observer, who likely doesn’t understand how the highly complex reparations loan scheme works in practice. The common perception of the situation is that the Russian cash can effectively be stolen and given to the Ukrainians, but this is not the case. Here’s the plan, step by step:

Belgian clearing house Euroclear transfers the roughly €175 billion in Russian assets it currently holds to the European Commission.

€35 billion will be used to cover already outstanding loans the Ukrainians owe to the G7.

The remaining €140 billion will sit in an EU controlled account.

The EU will issue a €140 billion loan to Ukraine that’ll be disbursed in tranches over an unspecified period of time. If German chancellor Friedrich Merz has his way, all of this money will be spent on weapons from the EU.

The Ukrainians will only be required to pay back this loan if the war ends and the Russians agree to pay them reparations.

The Ukrainians would then take this reparation money and use it to pay the EU.

The EU would repay Euroclear, and Euroclear would repay the Russians.

This complex series of moves is necessary because there is no legal mechanism through which the EU can outright seize the assets. Freezing them is legally possible – perhaps – under the UN’s Articles on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, or ARSIWA. These rules allow for a state to engage in otherwise illegal “countermeasures” intended to dissuade another state from engaging in its own illegal behavior. However, the form of countermeasures that can used for this purpose is limited to those that are “immediately reversible” once the state being punished ceases its illegal actions. The only other relevant provision is for countermeasures designed to provide “reparations” for an injury caused by illegal actions.

This makes the reparations scheme much more comprehensible. First, the EU won’t actually be confiscating the money, just issuing a loan theoretically backstopped by it. Second, the loan is, nominally at least, designed to provide reparations to Ukraine.

But the issues should be obvious. In order to maintain the “reversibility” of issuing a loan backstopped by the Russian assets, it must be theoretically possible that the Russians could recover the money the moment the war concludes (or, technically, the moment they cease their “illegal behavior”). If this were to happen, the Russians would have every right to demand the immediate transfer of the entire amount out of Euroclear, but it would have nothing but worthless IOUs from the EU on its balance sheet. In other words, the Belgians would be liable for somewhere around $150 billion of cash they would not have.

Another major issue is that the “reparations” the loan would theoretically provide wouldn’t come anywhere close to adhering to the definition of reparations as outlined in ARISWA. Those reparations are supposed to be for spending like repairing infrastructure. But German chancellor Friedrich Merz has publicly said that the entire amount of the reparations loan should be spent on weapons procurement contracts, ideally with EU firms.

Flagrantly violating the law could have severe ramifications that have been thoroughly outlined elsewhere, the biggest of which is triggering asset flight from EU banks in response to an apparent shift where EU (and UN) banking regulations could no longer be trusted. Scholars of international law are divided on these issues because there’s no precedent for anything like this. It’s debatable if the EU has any right to apply countermeasures at all, considering it’s not – on the surface at least – a party to the conflict.

To summarize the Belgian concerns:

The transfer of Russian assets they have custody of is illegal. As the legal custodian of the assets, Euroclear will break international law if they do so.

Once those assets are transferred, they’ll have to be treated as IOUs on Euroclear’s balance sheets.

They could be left fighting costly legal challenges from the Russians, potentially for decades.

If the legal challenges succeed, they’ll be the ones on the hook for repaying the Russians.

A veto from a EU country blocking the extension of the sanctions regime immobilizing the Russian assets (even temporarily) will give the Russians the right to reclaim the cash from Euroclear. Without a mechanism for refusing them, the Belgians would have no choice but to pay. Currently the sanctions regime must be extended by vote every six months.

Any possible solution to each of these concerns has major tradeoffs, and the only proposal that would seem to satisfy the Belgians is an airtight guarantee that the entire EU will backstop Euroclear. But with EU budgets already strained by deficit spending, this is an impossible ask.

One idea floated by policymakers both in and outside of Norway is using its sovereign wealth fund – the world’s largest – to backstop the loan. At over $2 trillion in value, ~$150 billion would be a relatively small liability for the fund, or so the thinking goes. On the 12th, the Norwegians dashed these hopes, citing fiscal responsibility regulations that would prevent opening up such a large liability to the famously risk-averse fund’s structure. Former NATO head, now Norwegian finance minister, Jens Stoltenberg said using the fund as the loan’s sole guarantor was “not an option.”

Meanwhile, the Financial Times gained access to EU documents outlining the dire situation the EU will face if it needs to put up the money for Ukraine’s loan itself, rather than confiscating the Russian assets. The Union will need to pay as much as €5.6 billion a year just in interest “indefinitely” to loan more money to the Ukrainians:

It said that if such a plan remains off the table, the bloc’s 27 member states must either authorise joint borrowing that would load up already strained national budgets with billions in fresh liabilities or provide Ukraine with direct grants totalling €140bn.

It added that both options would “potentially require fiscal adjustments in some member states” and “would directly affect their deficit and debt”.

The cost of servicing a joint-borrowed loan would run to as much as €5.6bn a year once the entire €140bn is borrowed and lent to Ukraine, the commission paper estimated, with heavily indebted France paying almost €1bn of that.

It added that Italy would contribute €675mn, and Belgium itself — which is already struggling to pass a national budget for next year — would shoulder almost €200mn a year in interest payments.

The commission document also warned that borrowing the €140bn could entail “potential knock-on effects both for market absorption and, notably, the rate that the Union will generally pay on its borrowing”.

“It cannot be discounted that it may also have additional indirect costs” for other EU finance programmes, it added

Yesterday, Le Monde dropped a major bombshell. Friedrich Merz announced his latest major proposal on issuing the reparations loan without even informing Euroclear, and the clearing house’s director Valerie Urbain found out about it when reading the news on September 25th. Given this, and the concerns outlined above, it’s understandable that the proposal has ruffled so many feathers in Brussels.

In the same piece, Le Monde reveals that the Belgians are hardening their stance in response to the enormous EU pressure on them to release the funds. Euroclear hasn’t ruled out suing the European Commission if it attempts to confiscate the funds:

If the European Union ultimately adopts a solution that resembles confiscation, Urbain said she is ready to respond in court: “There are laws. Depending on the legal framework, we will decide what we can and want to do.”

Does she envision legal action against EU bodies if Euroclear’s board believes its “fiduciary duties” are being compromised? “It is not out of the question,” she warned, while acknowledging that her teams have not, for now, prepared a case. Nevertheless, Euroclear has already had to strengthen its legal team since 2022, growing from about 10 to nearly 200 employees.

Belgian prime minister Bart De Wever has adamantly backed Euroclear’s leadership:

The Euroclear director can count on a key ally: Bart De Wever, the Belgian prime minister. Based in Brussels, the institution, a private company, relies on the Belgian Finance Ministry for sanctions. On October 23, late at night after the latest European Council, De Wever seemed energized after a day spent standing up to the rest of the 27 member states. “When you are a politician and you see a pot of gold [the frozen Russian assets], it’s irresistible,” he joked.

As head of the Belgian government, whose key role in international finance is owed to Euroclear, he opposes the Merz plan. “Is it legal? It’s not clear. (...) There is no precedent,” he noted, pointing out that even during World War II, central bank assets were not confiscated. In the event of a court sentence, it is Belgium that could be required to pay. “I am not able, and I do not want, to fork out €140 billion,” De Wever warned. He demands that each of the 27 member states guarantee the amount, in proportion to the size of their economy. “I asked my colleagues: ‘Who is ready to sign?’ I did not face a tsunami of enthusiasm.”

Urbain highlights the very real concern that EU renegades like Slovakia or Hungary will band together to block an extension of the sanctions regime that keeps the Russian money frozen. She also points to the billions of dollars in Russian funds held in diverse locations like Japan, the UK, and Switzerland. None of these states seem to be facing the scrutiny Belgium is. Meanwhile, the Russians have taken retaliatory measures by freezing between €20 and €40 billion of Euroclear client assets held by the Russian central securities repository. De Weaver: “I get calls from people saying, if you seize Russian assets, they will seize my factory, they will seize my frozen funds [in Russia].”

And Belgium is not the only EU state with concerns. An EU diplomat told the Kyiv Independent on the 13th that other member states are “hiding” behind Belgium, while Slovakian PM Robert Fico openly signals that his country will do everything it can to block the reparations loan. European officials are sounding the alarm that the IMF may divest from Ukraine entirely if the reparations loan isn’t pushed through

As Ukraine’s budgetary crisis looms, a steady trickle of EU funds continues to flow into the country. Germany has stepped up its projected unilateral aid from $10 billion to $13.4 billion in 2026. This increase will be funded by new debt. A new European Investment Bank loan totaling €200 million was issued last week to help plug the holes in Ukraine’s decimated energy infrastructure amidst a renewed Russian energy war campaign.

Meanwhile, the largest corruption scandal of Zelensky’s presidency is causing existential instability in the Ukrainian-EU relationship. Close Zelensky associate Timur Mindich has been accused by the US/EU-backed National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU) of embezzling up to $100 million in Ukrainian government funds through a series of bribes and kickbacks from energy contractors. Mindich is closely connected to Fire Point, the controversial Ukrainian defense contractor we’ve covered extensively. After having his Ukrainian citizenship cancelled, he fled to Israel, where he holds citizenship.

I’ve said previously that I believe the reparations loan scheme will go ahead despite opposition to it within the EU. Taking stock of the situation as it currently stands, this assessment may prove incorrect. The momentum in this case is now working against the scheme, as the Belgians dig in their heels, and seem to be capable of resisting all the pressure put on them by their neighbors. There is no clear solution on the horizon, no ace in the hole for the European Commission to play. As the situation degrades, the best path forward may be pointing the finger at the Ukrainians, rather than Belgium. A new wave of Zelensky-critical pieces in the Western media lends credence to this idea. But Zelensky has survived every other scandal he’s dealt with.

The only thing that seems certain at the present moment is that all these issues will eventually come to a head – likely soon. A combination of major battlefield setbacks, scandal, budgetary crisis, and the severe consequences of the energy war are pushing the Ukrainian-European relationship to its limits.

So Timur fled to Israel, eh? What. A. Surprise.

This is another facit of Russia's War of Attrition. I have argued in the past that the Russians are attriting Ukrainian manpower, and Western materiality and will. This is clearly a case of an example of material attrition. The EU states are in desperate financial straits, and the frozen Russian assets are the only spare cash left, only there is a whole lot of fishhooks if this is used. In the end, no Western state will want to face the consequences if the money is stolen for use in Ukraine, but in the end Ukraine ceases to be a functional state at the end of the war, unable to repay any loan which EU countries will have to pay back to Russia plus penalties.