Ukraine's Looming Budgetary Crisis

European political and financial leaders spent much of this past week deliberating on the possibility of making the $137 billion (or $208 billion, no one seems to be able to say for sure) in Russian assets held by Euroclear Bank available to Ukraine, which is in desperate need of large infusion of cash. The Ukrainians’ hopes were dashed, however, when the “marathon session” concluded the same way every meeting on this subject has so far: a future meeting has been set, no commitment has been made, with the Europeans saying “options” must continue to be explored.

The Belgians are the primary roadblock, as they play host to Euroclear, and are understandably nervous about crossing what amounts to the Rubicon for the European financial system. There’s no precedent for confiscating such an enormous amount of sovereign money, and potential legal challenges from the Russians compound with the disturbing thought that the rest of the world might no longer feel comfortable storing its money in European banks if the plan were to be implemented.

The EU’s current idea for how to steal the Russian money is to issue a “reparation loan” to Ukraine. After a Ukrainian victory, the Russians would be forced by the international community to issue reparations, paying the Ukrainians, who would then repay the loan. In this sense, the money isn’t being stolen at all, but is rather being borrowed from a future Russian state which will be too humiliated to protest. The majority of the loan would likely return straight back to the EU in the form of weapons contracts.

It’s understandable that the Belgians are skeptical of this scheme, as there’s no contingency for who will be paying up if the Russians refuse to, or, god forbid, the Ukrainians don’t achieve victory. Belgian Prime Minister Bart De Wever has publicly stated he’ll only get on board if the EU agrees to collectively back the loan if something goes wrong:

“If you want to do this, we will have to do this all together. We want guarantees if the money has to be paid back that every member state will chip in. The consequences cannot only be for Belgium.”

But this is easier said than done. It will likely require unanimity within the EU to achieve, or it would risk widening the growing fault lines within the union.

It is, however, well within the realm of possibility that a deal of some kind will be worked out in the not so distant future, because the complex game of financial musical chairs the Europeans are playing in Ukraine is in danger of coming to an end. And to keep the music going, they’ll need to start taking major risks.

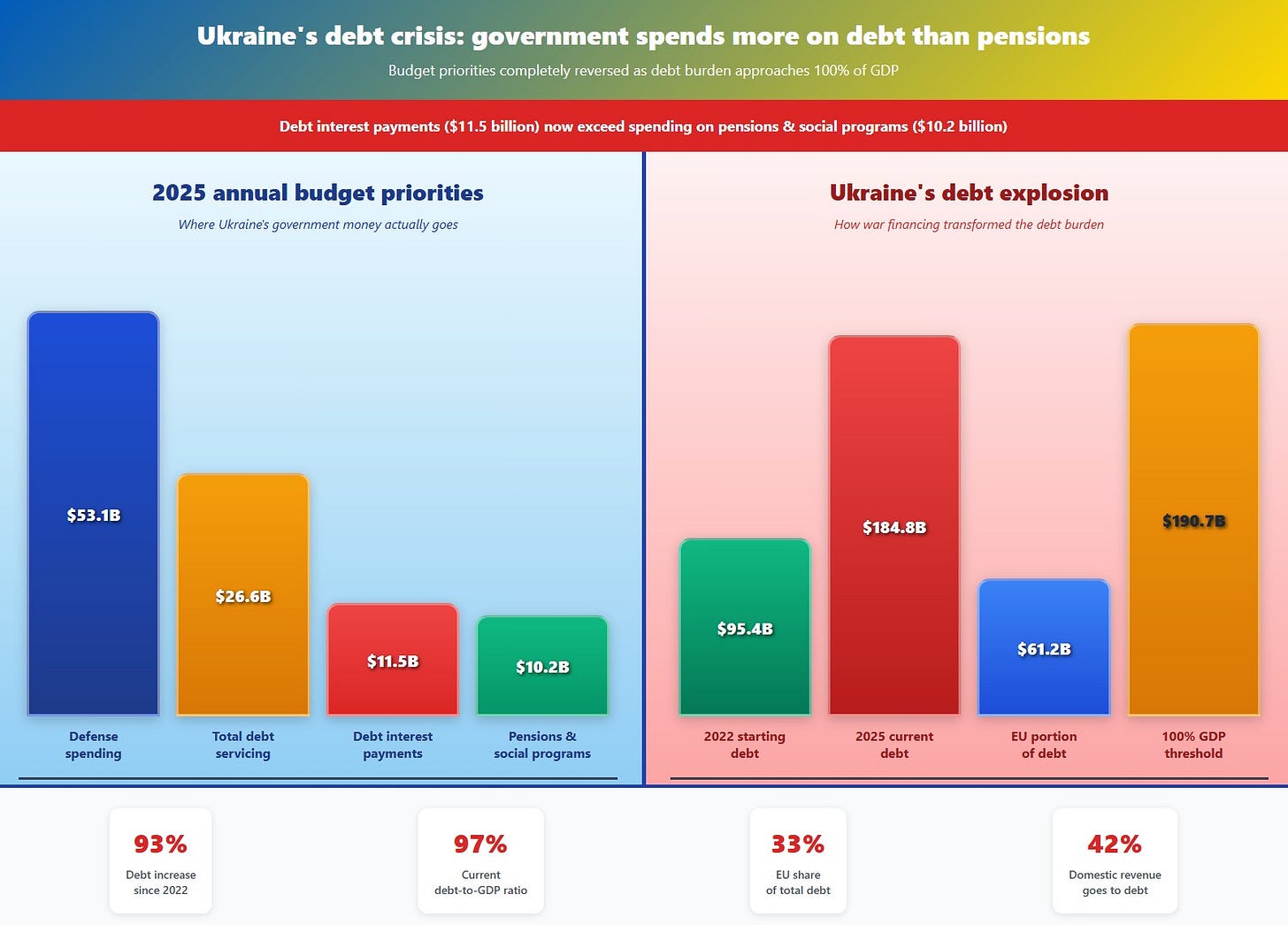

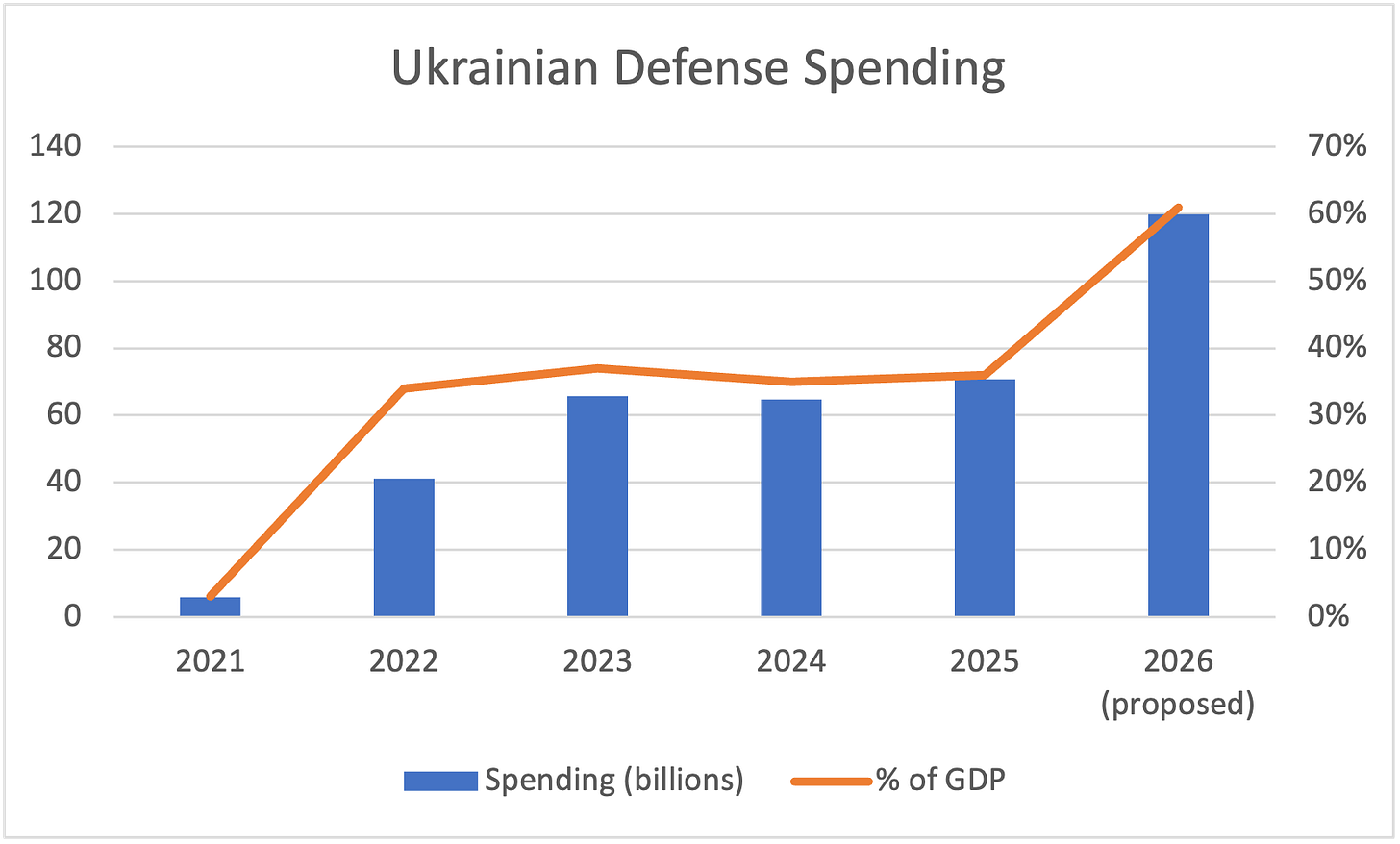

The Verkhovna Rada has passed two budget amendments this year, one in July increasing the Ukrainian government budget by $9.87 billion, and a second three days ago increasing it again by $7.7 billion. Both increases are entirely for defense spending, which will reach $70.9 billion by the end of this year, setting a new record. 63% of Ukrainian government spending is on defense, but this level of spending pales in comparison to the $120 billion both Zelensky and Defense Minister Denys Shmyhal say they’ll need in 2026.

This ambitious target likely hinges on unlocking confiscated Russian funds, as it will catapult Ukraine to a truly unprecedented level of spending for a state of its size. $120 billion would represent 61% of Ukraine’s GDP – the next biggest defense spender by this metric is Israel, at only 9%. It would become the fourth largest defense spender in the world, spending only 20% less in absolute terms than Russia ($149B in 2024) and 26% more than Germany, which is currently in fourth place.

In early September, the IMF – Ukraine’s third largest creditor – expressed concern that Ukraine has a looming shortfall in external financing of up to $20 billion. The current IMF package ($15 billion) has already been mostly spent, and Ukrainian estimates of needing another $37.5 billion in external financing over the next two years don’t seem to be enough. The lender has proposed various solutions, ranging from increasing taxes to reducing the salaries of AFU soldiers, but after a historic 2024 tax hike, the Ukrainians are running out of options. The IMF program assumed the war would end this year.

Ukraine’s next IMF loan is expected to be for a four-year term, and needs to be negotiated before the end of this year. The Ukrainians admitted the IMF projections are likely correct late last month, and the IMF shared the projections with the European Commission. With US support dwindling, the EU has taken over as Ukraine’s primary financial backer, but the Union’s ability to meet the IMF projections hinges on the frozen Russian funds sitting in Brussels.

If the EU can’t come to an agreement on utilizing the Russian funds, it isn’t clear how Ukraine will be able to fund itself past the first quarter of 2026. The Rada’s 2026 draft budget (which doesn’t account for the increased level of defense spending Zelensky aspires to) assumes a 58% deficit with a $50 billion shortfall. While new external loans will cover $31 billion of this, there’s a $19 billion gap for which no one seems to have a solution.

“We really would like to convince our allies that the EU reparation loan must be operational by the end of 2025 to avoid this financing gap and to ensure continuity of military and macro-financial support.” Iryna Mudra, Zelensky advisor

Kiev has tried to get creative, proposing that military aid to Ukraine could be counted towards NATO defense spending targets, despite Ukraine not being a NATO member state. They also suggested that the future profits on the confiscated Russian assets (the actual profits are already being sent to Ukraine) could be “anticipated” to backstop a new form of loan. Another idea is to reinvest the Russian funds into riskier asset classes in order to generate more profits. None of these proposals seem to have made much headway yet.

The Ukrainians have to get creative because issuing new bilateral loans is a tough ask. Ukraine’s gross external debt has ballooned over 100% since the war began, and now stands at $208 billion, over 100% of GDP. The vast majority of aid and financing given to Ukraine by its foreign partners and international financial instruments come in the form of loans, not grants.

“There’s growing concern about next year and many stakeholders that were banking on a ceasefire deal this year [to ease Ukraine’s fiscal strains] are having to recalculate their outlays and realising that there’s a [financing] hole whichever way they to try to slice it.” - EU official, FT

Ukraine is currently paying nearly four times more to service its existing debts, and on interest, than it is on social programs. Most of this is government-to-government debt, meaning it can’t be restructured like private debt.

This mounting pressure makes it very likely that the reparations loan plan will be implemented. Without it, a crisis could unfold in Ukraine as early as next year. EU states will be injecting the Russian money more or less straight into their own economies in the form of purchase contracts for military equipment. This places strong incentives for countries like Germany – which is dealing with the collapse of its manufacturing sector – to apply pressure to their Belgian neighbors to stop dragging their feet.

The long-term risk to the European financial system is potentially enormous, but Ukraine’s ballooning debt represents an equally dangerous time bomb. The EU is set to meet again on the reparations loan issue in December. For the Ukrainians, this is cutting things much too close for comfort.

I've worked in a place where contingencies were ignored because they'd be disastrous if they actually happened. This scheming to take sovereign funds looks exactly like that. They have no idea what to do when the Russians come for their money, as they will. All the EU compradors have in preparation for that are vibes and their own fumes.

Like America, UkroNam is bankrupt and beholden to shady banksterz, fraudsterz, con artists and bad actors who do distatateful things to poor helpless pianas, thieves murderers child killers and organ harvesters ....