Tit for Tat

On the Russo-Ukrainian energy attrition war

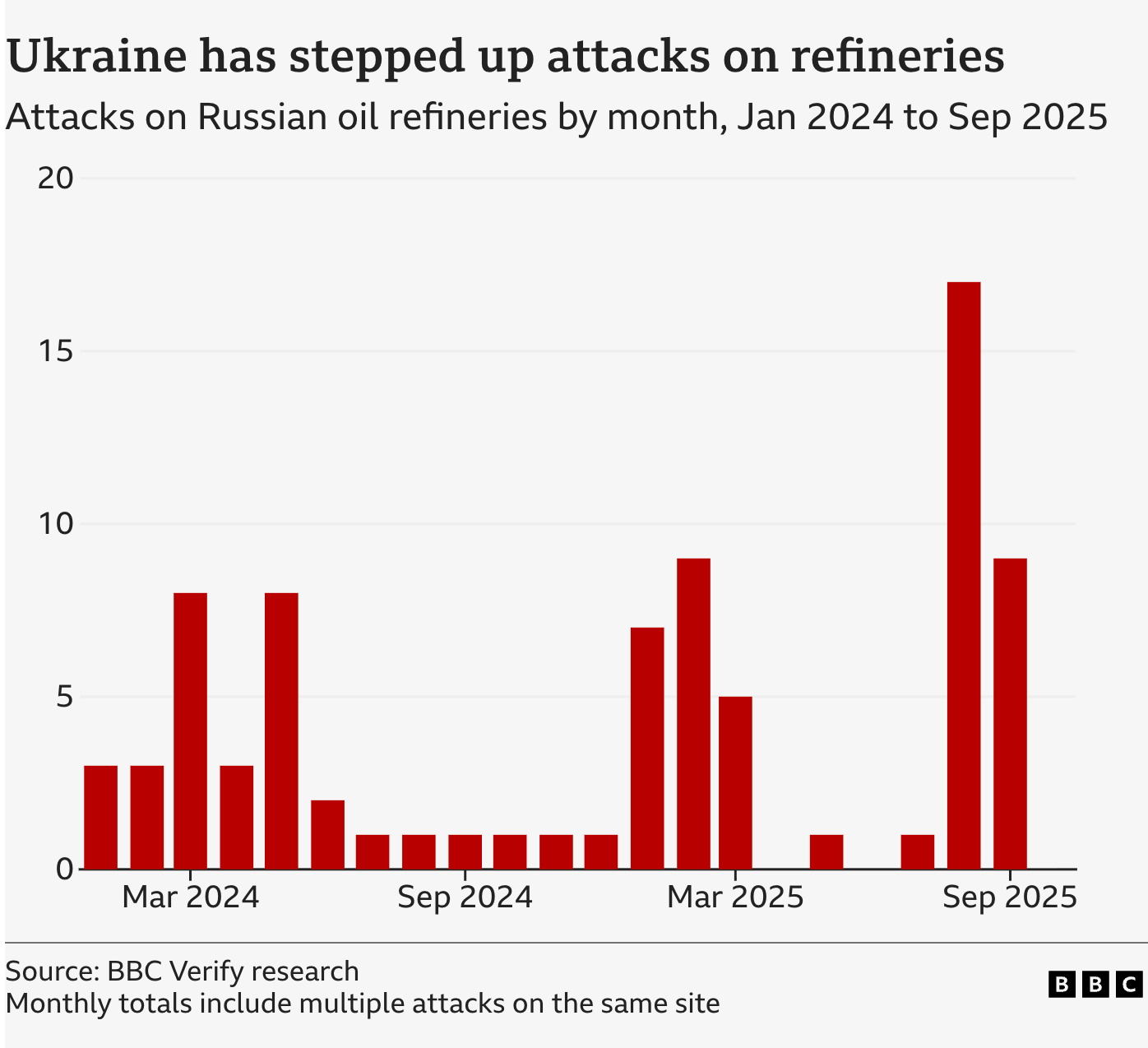

The Russo-Ukrainian War has entered a new phase. After an intense but short-lived drone campaign against Russian oil refineries in 2024, the Ukrainians have doubled their efforts in 2025, surpassing their 2024 total by August or September, with much of the year left to go. In response, the Russians have unleashed a missile and drone campaign of unprecedented scale and tempo, targeting Ukrainian electricity transmission infrastructure, gas production facilities, power plants, and rail assets. The reaction from observers of the war has been predictably split, with some saying the Russian economy is on the verge of collapse, while others believe the Russians have finally had enough, and are now determined and able for the first time to shut the power off in Ukraine for good. Crucially, neither side seems to show any sign of letting up, as each overwhelming Russian attack thus far has been followed more or less immediately by a Ukrainian attack of some kind. In this piece, we’ll break down the effects of the energy attrition war, and where it’s likely to go from here.

Ukraine’s Drone Campaign

Going purely off what can be gleaned from headlines, Ukraine’s attacks on Russian oil refineries appear to have struck a major blow to the Russian economy. 40% of Russian oil refining capacity is said to be offline due to drone attacks, based on widely circulated calculations.

A close analysis of reporting on this claim will show inconsistencies. Sometimes the ~40% figure is stated as “refineries,” rather than “refining capacity.” Sometimes 40% of Russian refineries or refining capacity is “idle,” sometimes “damaged,” or sometimes even “destroyed.” These descriptions gloss over the inherent realities of resource extraction, processing, and maintenance.

A key datapoint puts a serious hole in the triumphant headlines: around 22% of Russian oil refining capacity is sitting idle at any given time, whether due to maintenance, production limits, surplus capacity, or bottlenecks. Perfectly balancing the inputs and outputs of a complex chain of production across one of the world’s largest petroleum exporting countries isn’t possible, and so erring on the side of surplus capacity is the norm.

If 22% of Russian refining capacity being idle is a baseline, the effect of Ukraine’s drone campaign could maximally be a 16% increase in idle capacity. Reuters, likely the originator of the "38% offline” (typically rounded up to 40%) calculation, itself cites “extensive planned maintenance” as accounting for some of the offline capacity, though they don’t specify to what degree this adds to the total. How “extensive” this planned maintenance is will proportionally reduce the effect that can be attributed to the drone campaign. Russian sources put the current idle capacity at around 18%, slightly lower than the same period in 2024 but higher than in 2022.

The complexity of estimating the true effect of the Ukrainian campaign is compounded by the method of attack – typically small barrages of long range drones with small payloads. Without massed saturation attacks, and with attrition from air defense, only small sections of industrial sites can be struck, and the operational effect of any given strike can vary widely depending on what was hit. A strike on fuel storage may bring a refinery offline and start a large fire, but the site could be brought back online relatively quickly and with minimal expense. As an example, the Volgograd refinery, one of the largest in Russia, was struck on August 13th and 14th, but fully restored operations by August 25th.

Russia’s petroleum production mixture further muddies the waters. Gasoline, and gasoline shortages, have been pointed to as a key signifier of the efficacy of Ukrainian attacks. But Russia’s gasoline production pales compared to its natural gas and crude oil production, both of which it produces at roughly ten times the rate. 95-octane gasoline is particularly vulnerable to shortages, because the the Russian petroleum industry produces roughly as much as is required for domestic consumption. In comparison, Russia produces more than double the amount of diesel and almost triple the crude oil required to meet its domestic needs. So even if gasoline shortages are as widespread and severe as is claimed (the evidence shows they’re not), it doesn’t signal an existential issue for the Russian petroleum industry or economy as a whole.

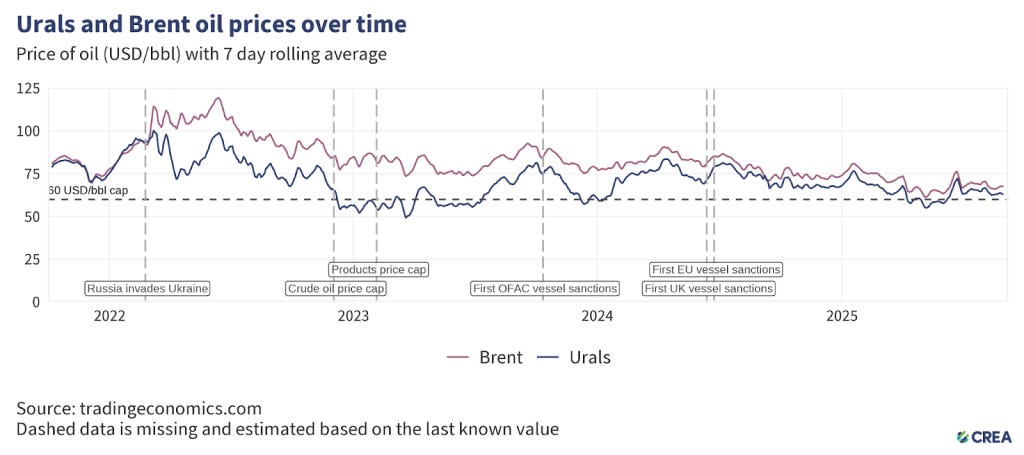

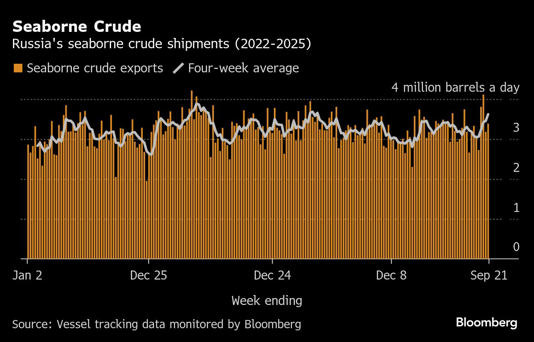

But are the effects of the drone campaign visible in Russian exports? In September, Russian crude oil exports hit a 16 month high. This may seem counterintuitive, but if the Ukrainians have disrupted refining capacity, Russian oil producers are incentivized to sell crude, which requires less processing. This shows that the Ukrainian attacks are having some effect.

But one other thing that can clearly be gleaned from this increase is that the Ukrainians have failed to significantly disrupt Russian pipeline infrastructure. The Ukrainians have targeted pumping stations and terminals with the same intensity as refineries, hitting sites transferring oil to the Black and Baltic Seas. But no decrease in Russian oil exports has occurred, suggesting quick repairs, redundancies, or spare capacity have made up for the difference.

Russian gas exports are similarly unaffected. Exports via Turkstream have increased 8% year over year, while gas revenues match general market trends. Europe remains Russia’s largest buyer of both LNG and pipeline gas. Revenues are down since the beginning of the year, but this is due to global oil prices and a strong ruble. Much has been made about Russia’s increasing budget deficit (1.7% of GDP), but even if it sees unprecedented overruns in 2026 it will remain lower than that of countries like the US (6%), China (6.5%), Brazil (8.5%), France (5.8%), India (4.8%), Turkey (4.9%), the UK (4.8%), or Ukraine (~20%). Similarly, Russia’s debt-to-GDP ratio is among the lowest in the world.

The bottom line is that the Ukrainians are simply not doing enough to achieve a strategic effect on the Russian economy. Some combination of low offensive capability, Russian air defenses, and the Russian oil industry’s quick response and excess capacity is preventing the drone campaign from severely disrupting oil production and export.

Too Little, Too Late

Low standoff weapon production is a likely culprit. Both the flagship FP-1 long range one-way attack drone and the much hyped FP-5 “Flamingo” cruise missile are manufactured by the Ukrainian firm Fire Point. FP is currently mired in a corruption scandal, as Ukrainian media outlets have fingered its enormous funding increases as an example of graft, and its weapon production figures as astronomical inflations. FP’s executive leadership has no experience in military industrial production, yet their government funded revenue has increased from $4 million annually to over $100 million in 2024, a staggering third of Ukraine’s budget for drones. Its leadership personnel are former entertainment industry veterans who are close to Andriy Yermak. Their funding is projected to reach $1 billion this year, primarily through EU grants.

AFU drone commander Yury Kasyanov has publicly identified previous Flamingo launches of being elaborate public relations stunts, with warheadless missiles being launched simultaneously with cheaper and more conventional one-way attack drones. Similarly, Fire Point’s claims that they’ve begun producing 50 FP-5 units a month and will reach a rate of 200 per month by the end of the year strain credulity, as the platform relies on complex jet engines (FP claimed to have “found” thousands of AI-25 engines in landfills across Ukraine). FP-1 production figures also defy belief. FP claims to be producing over 100 units daily, but this is the typical upper bound of how many drones Ukraine can fire into Russian territory in a day, and Ukraine’s drone arsenal includes dozens of other models.

Ukraine’s core problem in this regard has less to do with corruption than with the fundamental realities of its military-industrial complex. The vast majority of its weapons come from outside the country, being delivered from the surplus and obsolete stockpiles of its allies. Crucially, Ukraine’s allies do not possess vast quantities of one-way attack drones to donate, and Western military manufacturing is sclerotic and hampered by deindustrialization. Attempts to scale up domestic production have largely failed, with the key success story being the establishment of a cottage industry where Ukrainian civilians assemble commercial or 3D printed drones with surplus explosive warheads in their kitchens and basements, safe from Russian attacks.

Manufacturing large, complex drones and missiles of proprietary design in centralized workshops is another matter entirely. Just days after Ukrainian media posted photos of FP-1s under construction in an anonymous workshop somewhere in Ukraine, the same workshop was hit by a barrage of cruise missiles and destroyed, with unknown effects on Fire Point’s production rate. Even foreign manufacturers with deep pockets attempting to set up shop in Ukraine have found the prospect all but impossible – Baykar’s $100 million facility in Kiev was severely damaged by a Russian missile attack before it could come online, and Rheinmetall’s plans to construct armored vehicle and artillery shell factories in the country have never materialized despite years of headlines and planning.

Tit for Tat

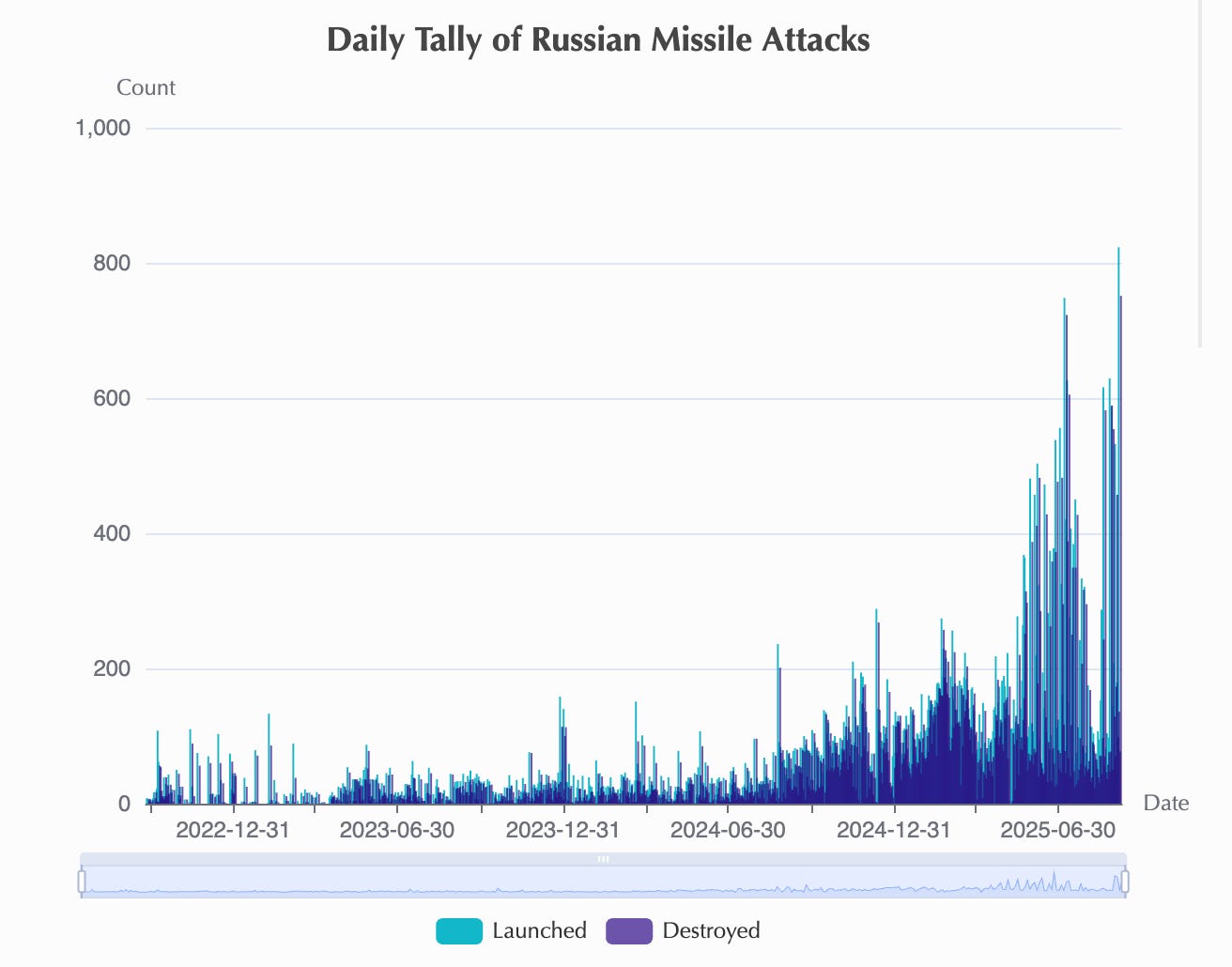

After introducing the Geran platform in the form of transferred Iranian Shahed-136 models in late 2022, the Russian military industrial complex has made rapid progress in drone production rates. 3,000 attack variants and decoys were produced in total in 2023, but that rate has exploded to a peak of 4,000 units a month in 2025. Steady updates have been made to the platform: doubled payload, jet engines, lighter airframes, more complex and jamming resistant avionics, real-time data links, evasive maneuvering, reduced radar cross section, increased range, image recognition based targeting, and mission-specific warheads. Increased production is obvious – while a typical strike package might have contained a few dozen attack drones in early 2023, in 2025 as many as 800 drones and decoys are being launched in a single night of attacks. Static launchers are being greatly expanded at the Navlya Training Ground in Bryansk Oblast, signaling that even larger strike packages are planned, or larger drone models are soon to be introduced.

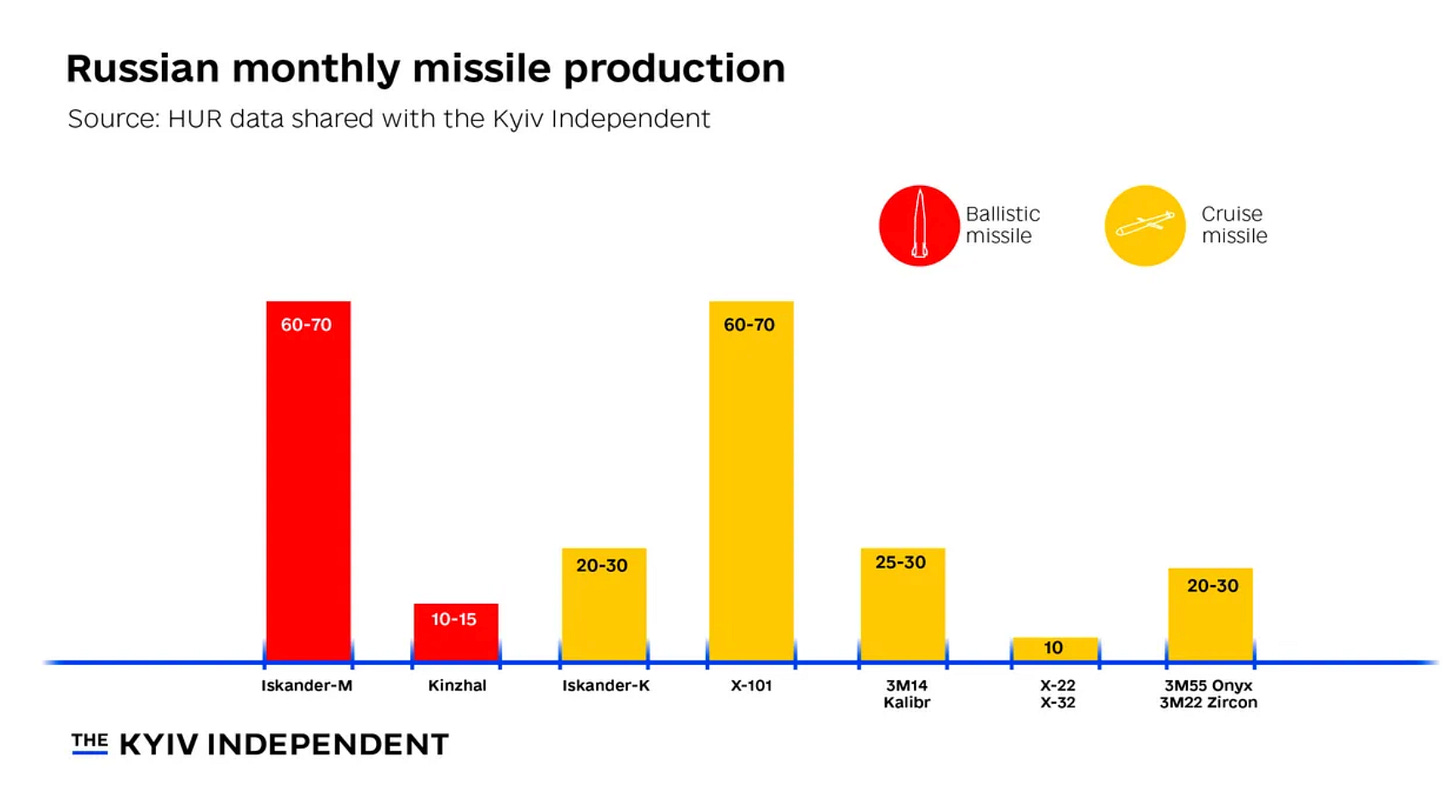

Russian missile production has ramped up similarly. Around 1,000 Iskander and Kinzhal missiles are being built annually, up to 40% higher than the Ukrainians estimated in 2024, and a 66% increase year over year. Kh-101 production has increased by 1,000% over the 56 units constructed in 2021. These numbers dwarf the rate of missile interceptor production of the entire combined Western military industrial complex, and only a small fraction of those interceptors are going to Ukraine. Even worse, air defense doctrine dictates firing at least two interceptors for every incoming target, and it’s an open question if Ukraine’s dwindling missile defense systems are capable of shooting down targets like the Iskander or Kinzhal with any consistency, or at all. The explosive payload of these missiles is typically five times or more that of a large one-way attack drone, and they’re significantly less likely to be shot down.

The Russian response to Ukraine’s drone campaign has become increasingly severe. We covered the attacks on Ukraine’s gas infrastructure last week, but this is only a small part of a comprehensive campaign targeting power plants, electrical transmission infrastructure, and rail logistics. Total blackouts have affected every corner of Ukraine over the past two weeks, as the Russian military fired a combined total of over 3,000 drones and a 100 missiles over the course of the single week ending October 12th, an all-time peak for the war so far.

Russia’s campaign against Ukrainian energy infrastructure has been ongoing since the early phases of the war, but has followed a clear progression of escalation. Smaller electrical transformers were targeted first, followed by larger ones. Power plants have mostly escaped direct targeting until now, with 13 plants being struck on October 9th alone. The systematic destruction of regional railroad infrastructure has progressed rapidly, with locomotives, depots, and electrical substations along rail lines receiving priority.

Balance of Power

A surface level reading of publicly available data suggests that the Russians are able to outpace Ukraine in standoff munition launches at strategic objects at a rate of around 3:1. All standoff munitions are not created equal, however. Russian missiles have vastly greater payloads than the average Ukrainian long range attack drone, and are more difficult to intercept. An enormous and growing asymmetry exists between the air defenses of the two combatants, meaning the Ukrainians must fire significantly more drones to achieve the same effect as a typical Russian strike package, due to losses. Ukraine operates a complex assortment of various drone platforms, but none of them are as technologically advanced as the Geran – especially not the latest variants – meaning they’re easier to jam and shoot down.

Just as importantly, all of Ukraine is within range of Russia’s triad of standoff platforms: cruise missiles, ballistic missiles, and drones. The distances Ukrainian drones have to cover to reach targets deep within Russia require design constraints and passage through layers of fully intact air defenses. Large swathes of Russian territory are inaccessible to drones launched from within Ukraine’s borders, forcing the Ukrainians to conduct risky and complex operations on Russian soil, or launch from the territory of Russia’s neighbors.

Precisely establishing the difference between Russian and Ukrainian standoff offensive potential in a long-term attrition war on strategic objects isn’t possible. The mixture of decoys and attack drones used by each side isn’t known, nor can the interception rates reported by the combatants be taken at face value. But respective military production rates and the geographic and technological realities at play suggest that it is within Russia’s ability to permanently collapse the Ukrainian energy grid, perhaps soon, while the Ukrainians do not have the ability to attrit the Russian grid outside of border areas like Belgorod, or deal a truly major blow to the Russian economy.

To close the gap, the Ukrainians will have to increase both the sophistication of their standoff arsenal and the rate of production by a factor of several times. They’ll need to procure large quantities of long range cruise and ballistic missiles with small radar signatures, maneuvering ability, and heavy payloads, and the platforms needed to fire them. There is no clear solution to this on the horizon. The Tomahawk platform is not a realistic option. Long range air-launched missiles like the AGM-158 JASSM-ER are not available in the quantities Ukraine needs, nor do Ukraine’s allies seem interested in providing them. And even if they were, Ukraine has a shortage of airframes, pilots, and uncontested airspace in which to launch them. Domestic design, implementation, and mass production of a cruise or ballistic missile platform typically takes over a decade, even for a much larger power in peacetime. The best the Ukrainians can hope for is scaling up production of a platform comparable to the Geran, but even if they manage to do so, the Russians have a years-long head start, and will likely have scaled their production even further in the meantime.

Strategic Considerations

Due to the overmatch at play, it may be surprising that the Ukrainians have chosen to escalate the energy attrition war. A deep analysis of Ukrainian strategy and victory conditions in this conflict will shed light on this subject. Given the progression of the front lines, Russian military production, inconsistent Western support, and demographic realities, the AFU is likely to suffer a full military defeat if the status quo is maintained. Given this, the best chance the Ukrainians have – and this has been true for most of the war – is to escalate the conflict to the point that additional military powers become involved.

The right balance of humanitarian concern, contrived provocations, public relations, and political maneuvering could potentially suck NATO or individual European states into the war. The likelihood of a stalemate or frozen conflict through this route is significantly higher than the AFU somehow regenerating its combat power, or the Ukrainian military industrial complex being able to procure from abroad or produce domestically some form of wonder weapon to turn the tide permanently in Ukraine’s favor.

With this assessment, any and all escalation becomes good escalation. Every indication shows the Ukrainians have no intention of slowing down their strikes on Russian energy infrastructure in response to the unprecedented Russian counterstrikes on theirs. Each new record-setting Russian attack has been followed more or less immediately by a renewed Ukrainian one. If the Russians do shut off the lights or heat in Ukraine, the resulting humanitarian crisis would be enormous, and it isn’t hard to picture the outcry that will be made to deploy “peacekeepers” or humanitarian workers from allied countries in response. Yes, a destroyed energy grid will affect AFU operations, but the greatest share of the suffering will fall on the Ukrainian civilian population.

Another key factor motivating the Ukrainian campaign is a simple asymmetry: Ukraine does not have the burden of maintaining a functional national economy. Ukrainian exports are a fraction of its neighbors in monetary terms, and near-unlimited access to loans, grants, and aid allows more than half of the Ukrainian government budget to be paid for by other countries. This is not the case with Russia, which must pay for repairs to its infrastructure itself, and maintain competitive prices for its exports.

Russian hesitancy to fully destroy the Ukrainian grid has caused confusion among observers. A common refrain is that they should have done this “on day one,” but Ukraine’s Soviet energy infrastructure is notoriously robust, and composed significantly of rock-solid hydroelectric plants and politically unassailable nuclear power plants. The vulnerable points of the system are scarce, expensive, and hard to transport electrical transformers, which the Russians have been attacking for years, while always holding back from dealing a killing blow.

As mentioned previously, the Russians attacked the least expensive and important transmission infrastructure first, which is the opposite of what one would do if the intention were to collapse the grid. The logical conclusion then is that the Russian strategy in the energy attrition war is to slowly escalate as a form of deterrence, taking care to avoid a true humanitarian crisis, which would redound to the benefit of the Ukrainians. Instead, the slow ratcheting up of pressure has given the Ukrainian population ample time to exit the country and prepare, reducing the impact of a crisis if one were to occur. Meanwhile the Ukrainian grid has been made more and more vulnerable over time, while the Ukrainians and their European sponsors have had to exert great expense and effort to keep it functioning.

The Russian strategy hasn’t worked, because the Ukrainians have begun to call their bluff in earnest. AFU planners are aware of Russian offensive potential, but have plowed forward with the energy war all the same. The state of the Ukrainian grid is now dire, with the Russians having the ability to impose blackouts in large cities like Kiev or Kharkov at will, or near-full blackouts of the entire country with exceptionally large attacks. Because the Ukrainians have shown no signs of being deterred, the only possible direction the situation can go is towards further escalation.

The key questions for Russian planners are: can the risk of plunging Ukraine into darkness during the winter be taken? Will the resulting catastrophe cause the conflict to spill over into something larger? Or should the Russian economy take the refinery strikes on the chin and keep marching forward as before towards a likely victory that could be a year or more away?

Ukraine isn't being run in the interests of its own population. The question is why does US/NATO order them to a strategy of suicidal escalation and the answer is the better informed among the planners who direct Kiev expect Kiev to lose to a meaningful degree (like RF territorial goals attained, with possible substitution of Kharkov parts for right-bank Kherson). Therefore Kiev is tasked with a simple pair of goals (1) do as much damage to Russia as possible, (2) leave as little salvageable left at the end of the war as possible - including slaughter of the male population.

The war will thus end thru simple human exhaustion, and this is a deliberate choice of Ukraine's Western sponsors. Nobody wants to see populations getting displaced by lack of electricity, but their intended fate is to make a show of getting killed for the benefit of the US. They're frankly better off in the safety of an EU country than under the Ukrainian regime.

As for the potential for escalation to "work" in the sense some Ukrainians might wish it to, it isn't actually there. The relevant NATO countries who could plausibly be tricked into fighting and produce meaningful scale (like primarily Poland and Turkey) have apparently caught on and are content to send arms. That isn't going to happen. Russia is also far from alone in this, China - despite their arms-length posture and apparent frugality - is in a very meaningful conflict with the US, and serves as a robust commercial backstop in exchange for Russia doing the same for them in material and geostrategic terms. This will continue as a costly and bloody fight, but little chance it escalates. Where that can and probably will happen is Iran.

Nobody in Washington, nobody in Brussels, nobody in Kiev cares in the slightest whether Ukrainians freeze or starve. The only thing Ukraine produces is warm live bodies.

Russia is basically wasting missiles.