Patriot Games

An Evaluation of Western Wunderwaffen in the Ukraine War (Part 5)

We'll continue with the second piece of hardware in this series to receive its own full article. Just as the story of the Leopard 2 was intertwined with the story of the Ukrainian 2023 Summer Offensive, the Patriot's story is inseparable from the history of air defense in the war, Russia's standoff weapon arsenal, and General Sergey Surovikin's strategic missile campaign. The Patriot's saga is much more complex than the story of the Leopard 2 or any other system we've covered. Unlike the stories of other systems, which tended to follow a predictable cycle of hype followed by stark collision with reality, the Patriot's carefully manicured public perception has clung on for nearly two years after its introduction. Attempting to understand its performance requires penetrating the thickest web of propaganda and censorship to surround any weapon system used in the conflict. The layers of obfuscation shouldn't be surprising because, as we'll discuss below, the efficacy of air defense, as seen in the war in Ukraine, has far-reaching consequences on military strategy, politics, and the survival of entire nations.

If you haven't already read the previous entries in the series, you can start with part one below.

Raytheon MIM-104 Patriot

First referred to as a game changer: July 2022

Appearance in Ukraine: April 2023

Country of origin: USA

Unit Cost: $1B-2.5B per battery, $2M-10M per interceptor

Number sent: 3 batteries, 4 additional launchers

Manufacturer market cap: $161B

The Air Defense Gap

On February 8th, 2022, sixteen days before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the British defense think tank Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), released a paper titled Ukrainian Air Defense Options in the Event of a Russian Attack. In the paper, RUSI describes the "disparity of forces in the air domain" facing the AFU if conflict – at that point looking increasingly like a possibility – were to occur. The Russians would have at least a 3:1 advantage in fixed-wing aircraft with the assets they had immediately available in the theater, and the differences in air defense assets were even more concerning. At the time, the Ukrainians exclusively operated modernized Soviet systems, including the long-range S-300 missile system, the medium-range Buk M-1, and the short-range 9K33 Osa. Their interceptor missiles and radars were a generation behind the Russian air defense systems at least, and spare parts for maintenance were unavailable due to restrictions from the eight years of conflict in the Donbass. Their age also precluded them from being joined together in a modern, integrated, and networked air defense system. Despite these limitations, the sheer number of systems in the country gave Ukraine the densest air defense network in Europe at the start of the war, in terms of launchers per area.

While the RUSI paper focused on the threat posed by Russia's Air Force (VKS), an initial wave of losses of air assets on both sides during the early stages of the war would result in planners scaling back their use. The Ukrainian Air Force (PS ZSU) lost a staggering 44 fixed-wing aircraft (1/3rd of their MiG-29s and 1/8th of their Su-27s) from shootdowns and Russian missile strikes on airbases in the first 48 hours of the war. The VKS got off relatively easy in comparison – and established a limited degree of air superiority – but suffered over a dozen losses of fighter aircraft over the next month, with most losses of medium and high altitude aircraft likely caused by Ukraine's 100 S-300 systems. The VKS responded to these losses by reducing medium and high altitude incursions into Ukrainian airspace, leaving the exceptionally durable Su-25 to operate at low altitude in a close air support role, where its principal threat would be MANPADS.

Simultaneously, Russian forces in Ukraine prioritized the destruction of the AFU's S-300s. Six weeks into the war, 21 launchers were confirmed as destroyed, roughly 7% of the AFU's stock. With the actual number of destroyed systems likely being many multiples of that number higher, Ukrainian air defense forces were suffering an unsustainable attrition rate and were unlikely to make it through the year with significant capability remaining.

Zelensky reached out to the Americans specifically for assistance in replacing their S-300 losses, but delivering air defense systems wouldn't be as easy as other types of military hardware. Israel blocked the transfer of American-owned Iron Dome batteries to the Ukrainians to avoid provoking the Russians, and the Iron Dome couldn't serve as a stand-in for the S-300 anyway due to its short range. Similarly to what would later be done with main battle tank transfers, the Americans attempted to arrange swap deals with allies to transfer their S-300s to the Ukrainians in exchange for Patriot systems. However, only three NATO member states operated the system: Bulgaria, Slovakia, and Greece.

Turkey publicly balked at the proposal they swap a Patriot for their Russian S-400 system. Their rejection of the plan was part of an inter-NATO feud in which the Americans attempted to strong-arm them into switching over to the Patriot in exchange for reversing their suspension from the F-35 program due to their purchase of the S-400 (there were serious concerns that the Russians were using it to gather data on NATO aircraft). They said they would accept Patriots and F-35s only "without precondition." At the end of March, Slovakia agreed to swap their single S-300 battery for a German Patriot battery, with Prime Minister Eduard Heger saying it was "the equipment that Ukraine needs the most." The transfer was completed in early April.

A week later, the Russian MoD reported it had destroyed multiple S-300s, including launchers provided by "a European country."

Sending the Ukrainians their own Patriot batteries was completely off the table, and the Biden administration said so explicitly in early March. Echoing statements US officials would later make to explain why it wouldn't be possible to send the Ukrainians the M1 Abrams main battle tank, the complexity and difficulty of operating the system were cited as key factors. The Patriot is so complex, they said, that only American troops would be capable of operating it.

“There's no discussion about putting a Patriot battery in Ukraine. In order to do that you have to put U.S. troops with it to operate it. It is not a system that the Ukrainians are familiar with and as we have made very clear, there will be no U.S. troops fighting in Ukraine.” - US official, March 2022 (Defense One)

Whether this statement is true is something we'll discuss later. Another explanation may have been cost. Modern air defense batteries are among the most expensive and sophisticated systems fielded by modern militaries. The export cost of a full Patriot battery exceeds $2.5B – a fifth the cost of a Gerald R. Ford-class supercarrier – while a single interceptor costs from $6-10M. Delivering even one Patriot battery to Ukraine would have represented an unprecedented escalation in aid over the low-cost, surplus, and obsolete systems that had been transferred up to that point.

"Alternative options are working with other allies and partner nations around the world who may have additional air defense capabilities and systems at their disposal who might be willing to provide them to Ukraine. And so we're having discussions with many countries right now about some of those capabilities, surface-to-air missiles for instance, that the Ukrainians are more trained and more equipped [on].” - John Kirby, Pentagon Spokesman, March 2022 (Defense One)

Even transferring the S-300 wasn't an easy task. Just like the Patriot, a "battery" includes multiple launchers, a command post, target acquisition radar, fire control radar, support vehicles, and the interceptor missiles themselves. Into the 2010s, the S-300 was described as "one of the world's most advanced" air defense systems, though the difference in performance between Soviet-era models and modernized variants is significant.

Missile Crisis

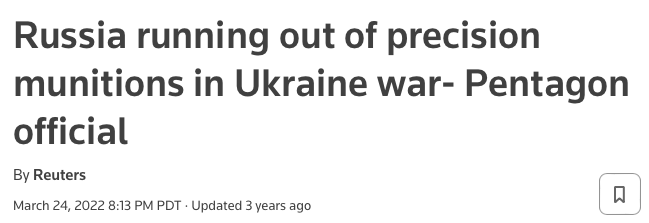

While the Ukrainians attempted to hash out deals with the Bulgarians and Greeks for their S-300s, their remaining air defense systems were left to cope with a bigger threat than VKS incursions into their airspace: Russia's strategic missile campaign. The Russians had made advanced standoff weapon capability a cornerstone of their military planning since the collapse of the USSR, and the investment had paid dividends. In the first 48 hours of the invasion, the US Department of Defense estimated the Russians had conducted 160 missile strikes on Ukrainian territory. By the first week of March, that number had grown to 775. The next week, the Western media reported that the Russian Iskander-M short-range ballistic missile (SRBM) is capable of dropping decoys to prevent its interception.

"The devices are each about a foot long, shaped like a dart and white with an orange tail. Each is packed with electronics and produces radio signals to jam or spoof enemy radars attempting to locate the Iskander-M, and contains a heat source to attract incoming missiles. The use of the decoys may help explain why Ukrainian air-defense weapons have had difficulty intercepting Russia’s Iskander missiles." - New York Times, March 2022

The Iskander is a system, not a specific missile. It includes a highly mobile launch carrier vehicle that is capable of firing a variety of missiles, including cruise missiles and quasi-ballistic maneuvering missiles with high-explosive, fragmentation, submunition, bunker-busting, fuel-air explosive, EMP, or nuclear warheads. The maximum missile payload exceeds 1,500lbs, and its burn-out velocity is Mach 5.9 – low hypersonic. Its inertial guidance system makes it largely immune to jamming.

The Pentagon claimed the majority of the missile strikes in the first 48 hours of the invasion were Iskanders. The missiles were primarily used against logistics nodes and command and control infrastructure within its 300-500mi range to disrupt AFU communications. For longer-range targets, the Russians typically utilized the Kalibr family of land-attack cruise missiles (LACM), which travel much more slowly than ballistic missiles like the Iskander-M and take a flat trajectory. Typically launched either from naval assets in the Black Sea or from strategic bombers, the >1000mi range of the Kalibr places the entirety of the territory of Ukraine within its targeting area. Once the war began, dozens of videos of Kalibrs – easy to film because of their slow speed – crisscrossing the country were posted.

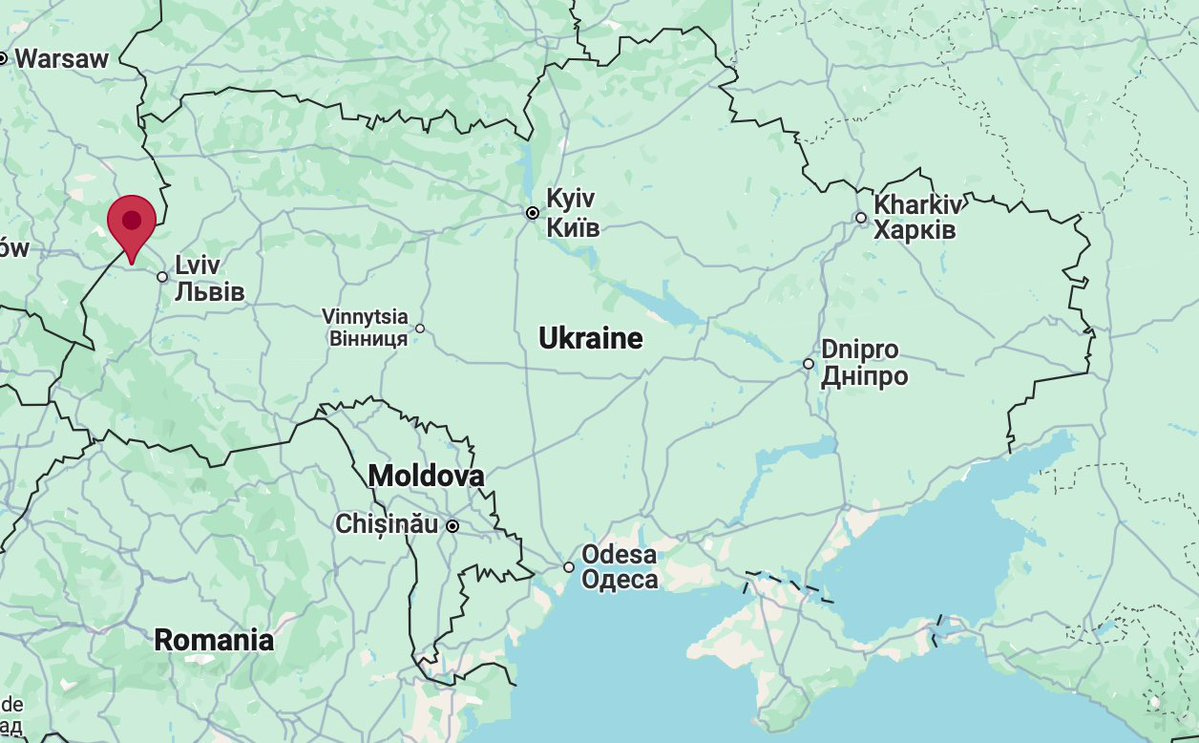

On the 13th of March, a large barrage (30, according to the Ukrainians) of Kalibrs struck an AFU base outside Lvov in Western Ukraine that was being used as a training area for over 1,000 Ukrainian Foreign Legion volunteers. Hundreds of foreign fighters, including British ex-special forces, were killed or wounded, and large quantities of recently delivered aid were destroyed. The attack sent shockwaves through the foreign volunteer community due to the scale of the losses and the proximity of the strike to the Polish border – a mere 10 miles. The Russians had demonstrated they had the capability to conduct precision strikes anywhere in Ukraine.

On the 18th of March, the Russian Ministry of Defense announced the first combat use of a hypersonic missile when their Kh-47M2 "Kinzhal" (literally "Dagger") struck an ammunition depot bunker in Western Ukraine. The next day, they used it again on a fuel depot in Konstantinovka. The performance of the Kinzhal would become a hotly debated topic in the Western press. Compared to the more advanced scramjet-powered Zircon, the Kinzhal is relatively primitive, being essentially a souped-up, air-launched Iskander – itself already hypersonic in some stages of flight – with slightly less than double the top speed. But military analysts recognized that the prospect of any air defense system intercepting a missile traveling in excess of Mach 8 was dim.

"[The Kinzhal] is a consequential weapon, but with the same warhead on it as any other launched missile. It doesn't make that much difference except it's almost impossible to stop it. There's a reason they're using it." - Joe Biden, March 2022

Opsec

As early as May, a pattern that would soon become familiar emerged in the media coverage of the Russian missile campaign. On the 16th, a salvo of Kalibrs targeted infrastructure and military aid deliveries in the Yavoriv region near Lvov and the Polish border. While initial Ukrainian reports indicated that a key railway from Poland had been hit - aligning with the statements of the Russian MoD - subsequent statements by local officials and online commentators said that every one of the eight Kalibrs launched had been successfully intercepted. Any damage, they said, was caused by falling debris.

Blurred videos taken by local residents were inconclusive (air defense interceptors like the S-300's 48N6 are supposed to self-destruct if they fail to find their target, resulting in an explosion in the sky, whether the interception happens or not). Local officials urged residents not to film or post videos of air defense operations.

In late March, President Zelensky signed into law a Rada bill criminalizing video dissemination of AFU movements and air defense operations. A week before, a Ukrainian citizen was detained for posting a video to TikTok in February of a Ukrainian MLRS and rocket ammunition being hidden beneath the parking garage of the Retroville shopping center in Kiev. In the middle of the night on the 20th of March, the Russians struck the parking garage with an Iskander, destroying much of the mall.

While the incident would be used to garner sympathy in the Western press, the message to everyday Ukrainians differed. Despite the Russians having publicly posted a video of UAVs following the MLRS from its firing position all the way back to the mall, the blogger was made an example of, and a video of his apology was posted by the SBU.

In the same period, Chinese national and Odessa resident Wang Jixian drew headlines and glowing profiles for his war reporting and vocal defense of Ukraine. Wang faced immense backlash from the Chinese language internet, and Western media outlets underscored that he had courageously chosen to take a stand by offering a rare pro-Ukrainian perspective to his countrymen.

In a video posted to Youtube in March of 2022, Wang covered his mouth with black tape to protest his censorship on Chinese social media

I want to (provide) some voice for the people in Ukraine, for the heroes, for my neighbors. Because in my eyes they are all heroes. I see people being calm, I see people brave … I want to remind you to see who is dying, who has been killed... I have no interest or desire to leave Ukraine until the war is ended and Ukraine has won. - Wang Jixian

But in October of 2023, Wang's daily posts suddenly stopped. Two months later, Ukrainian media reported that he had been sentenced to five years in prison for posting videos of air defense operations in Odessa. Luckily for Wang, the sentence was suspended, and he would be allowed to serve a year of probation instead. He had, however, received the SBU's message loud and clear:

"The old Wang Jixian is dead, I'm a 'new person' now. I hope for peace and no more wars. I will not talk about wars or politics anymore. I just want to be an ordinary good husband and spend all the time with my wife. - Wang in a post on 12/01/23

Many more examples of prosecutions of Ukrainians who posted videos of air defense operations, including in Odessa, cropped up as the war progressed. Accordingly, once-plentiful videos of Russian strikes on Ukrainian targets became rarer, and the interception rate claimed by the Ukrainian Air Force crept upward towards 100%. Videos posted of strikes within Ukraine had an ever-increasing area of the frame blurred out. In this environment, it was often impossible to reconcile the contradictory claims of Ukrainian and Russian reports on the results of strikes.

Supply and Demand

Predictions in the Western media that Russia had run out or would run out of standoff weapons in the initial weeks or months of the war were revealed to be wrong. While the Financial Times proclaimed that the Russians were "short" of missiles in late April, the Russians fired 48 Kalibrs in a single night at the end of June. The invasion wave of strikes – especially of Iskanders – had put a serious dent into the Russian missile stockpile. But either that stockpile was much larger than what Western analysts had estimated, or Russian military production had ramped up much faster than anyone expected. Fallen debris from shot-down Kalibrs revealed that Western electronics were still finding their way into Russian missiles, meaning that sanctions on their export were being subverted.

A report by Reuters and RUSI suggested that Russian imports of microelectronics had even increased since sanctions were applied. Assertions that Kh-101 production rates were as low as three a month were revised upwards to one every four days. The Russian government had taken missile production seriously, and factories that once operated on a four-day workweek switched to round-the-clock production in three shifts a day.

Weeks-long lulls in strikes – during which comments that perhaps the Russians had finally run out of missiles after all would return – would be followed by massive barrages featuring dozens of cruise missiles, with Iskanders and Kinzhals used for high-priority targets. Ukrainian air defenses stood little chance of repelling these saturation attacks. As the war progressed into the summer, Russian strikes crippled Ukrainian fuel infrastructure, destroying the country's two largest oil refineries.

By the fifth month of the war, Ukrainian authorities estimated that the total number of missiles fired at the territory of the country exceeded 3,500. However large the AFU's stockpile of interceptor missiles was, the standard air defense doctrine that two or more interceptors must be fired to have a decent chance of intercepting any given projectile meant that it was only a matter of time before the AFU ran out. Rationing interceptors could only be done by leaving many important military and infrastructural targets undefended. If the strategic missile campaign was going to turn into a war of attrition, the Ukrainians were destined to lose, especially as Russian military production ramped up. It would be crucial that the West provide some solution to the AFU's dwindling supply of interceptors. Luckily, Russian missile production appeared likely to remain low enough for the foreseeable future that they would remain incapable of dealing a knockout blow. The Ukrainians took steps to decentralize their logistics to limit the effect of any single strike.

Geraniums Bloom

In early October of 2022, Russian sources reported that General Sergey Surovikin had been promoted from commander of the Southern Grouping to commander of all Russian forces in Ukraine. Surovikin was instrumental in turning the Syrian Civil War in favor of the Syrian government and was the first combined arms commander in Russian or Soviet history to take command of the Air Force. Surovikin would also be the first member of the Russian military to be explicitly labeled the overall commander of their forces in the war. Western insight into the structure of the Russian Armed Forces is notoriously myopic, and while the appointment came as a surprise, it quickly became apparent that Surovikin's promotion had been in the works for months, and he developed a dramatic plan for forcing the war into a new phase.

The first pillar of Surovikin's plan was to consolidate Russian lines with painful withdrawals and dig in for a Ukrainian offensive in the spring of 2023 (read more about this in my article on the Leopard 2). The second was to unleash a massive strategic missile campaign to cripple both Ukrainian logistics and the country's energy infrastructure. Degrading energy production – which is inherently centralized and impossible to conceal or move – would be vastly easier than attempting to destroy hundreds of dispersed and hidden AFU targets. Sources in the Russian military said Surovikin was "not sentimental" and had earned the nickname "General Armageddon."

Surovikin's missile campaign would hinge on the introduction of a new type of weapon – one of the few that would truly earn the right to be dubbed a "game changer" in the conflict: the Iranian HESA Shahed 136, or as the Russians would call both the models procured from Iran and those domestically produced under license, the Geran (literally "Geranium"). In August of 2022, rumors began to circulate that a batch of Shahed 136s (or the similar 131/Geran-1 model) had been sent to Russia for military trials in exchange for a crop of Iranian pilots beginning training on the Russian Su-35 4th generation multirole fighter. Such a deal represented a win/win for the two countries, as the Iranians had failed to procure new fighter aircraft for decades due to sanctions, and the Russians did not have an equivalent to the Shahed 136 in their arsenal.

The Shahed (literally "Witness" in Persian) 136 was an example of the kind of military engineering ingenuity that is bred under resource constraints. Iranian planners recognized early that investment in air defense and standoff weapon systems could potentially make up for a lack of aircraft capability and had – like the Russians – prioritized those systems. Without modern fighter aircraft, fighter-based suppression of enemy air defenses (SEAD) – the process through which specialized fighters like the US EA-18G Growler and anti-radiation missiles like the AGM-88 HARM destroy air defenses through detection of radar – as practiced by powers like the US would be impossible. It would be necessary to instead rely on saturation attacks where enemy air defenses would be confronted with more targets than they could engage.

But such attacks – as the Russians had learned – are expensive and difficult to maintain in a protracted conflict. Cheap ballistic missiles have limited utility against military targets due to their inaccuracy, and more expensive missiles can only be produced in limited numbers due to their complex guidance systems, control surfaces, and jet engines in the case of cruise missiles. The Russians had already run into this problem in Ukraine. Even large salvos had no more than 50 missiles, and while production was increasing, it would take years before new targets could be met.

Enter the Shahed series. The Shahed's origins were described as "obscure." It had been developed years before the conflict in Ukraine, but the Iranian military kept the program under a veil of secrecy. There were rumors that it was the "unknown delta wing UAV" used by Ansar Allah in a 2019 attack on Saudi oil installations and in a strike on an Israeli oil tanker in the summer of 2021. In September of that year, Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennet announced the name of the system for the first time, saying the 136 "can attack any place any time."

No particular technological aspect of the system was new or even unique. The Americans, Israelis, and the Iranians themselves had produced platforms with similar capabilities since the late 1980s. The initial strategic thinking behind early concepts, like the American AGM-136 "Tacit Rainbow," was that anti-radiation sensors could be placed in slow-moving, loitering cruise missile platforms. These weapons could eliminate the enormous risk of fighter-based "Wild Weasel" SEAD tactics as Soviet air defenses became increasingly sophisticated. The AGM-136 program ended in failure, but like many doomed experimental US weapon programs, it predicted the future of warfare decades in advance.

What was new about the Shahed was that the Iranians had optimized the drone for cost, produced them in large numbers, and created a new role for it in standoff strategy. While its maximum warhead mass is around 90kg, roughly a fifth that of the Kalibr, estimates of domestic production cost for the Geran-2 are as low as $10,000 per unit, meaning as many as 100 Gerans could be produced for the cost of a single cruise missile, with no difference in precision. It would be possible to launch drone "swarms" with strategic-level effects for the first time.

The Shahed 136 is ingenious in its simplicity. This, combined with its almost uncanny accuracy, long range and low cost, makes it unique among strategic standoff weapons. Its airframe, made from carbon fibre cloth and honeycomb, can effectively be manufactured by any DIY handyman. Its piston engines are Iranian copies of civilian engines developed for air enthusiasts and the modelmaking market, and as such can be traded free of any export restrictions. The Shahed 136 avionics systems are largely based on commercial-grade products that are traded freely around the world. It navigates using a combination of a commercial-grade inertial navigation system together with GPS and GLONASS satellite navigation systems. It also carries a commercial-grade digital communication device that allows it to receive updates on its target’s location or even change targets. - RUSI

The strategy would work like this: first, a large salvo of Gerans is launched. With a top speed of only 115mph, it might take them hours to reach their targets. Meanwhile, strategic bombers loaded with cruise missiles take off from distant airfields. As the drones approach their targets, the much faster cruise missiles are launched so that their arrival coincides with the arrival of the drones. The Gerans may maneuver continuously throughout the attack, doubling back or circling over an area to maximally distract air defenses. And if the Ukrainians choose to ignore them, they present a serious threat in their own right because their warhead contains as much explosive as eight 155mm artillery shells. Smaller preliminary salvos of Gerans also allow for SEAD, as air defenses engaging them can then be targeted by ballistic missiles before they have a chance to pack up and move.

The Shahed 131/136 epitomises the democratisation of battlefield precision. By exploiting low-cost commercial and dual-use technologies and components, it has achieved a breakthrough in combining precision with affordability. Its range of about 1,300 to 1,500 km is adequate for theatre operations. Its small warhead is about one tenth of that of legacy cruise missiles – but this is compensated by its spectacular precision and even more so by its cheapness, which makes it widely available. No matter how many of them the Ukrainians shoot down, the few that penetrate their defences cause immense damage, and there are always more of them buzzing in for the next attack. Their prevalence, derived as it is from their low cost, makes defending against them an almost Sisyphean labour. The Shahed 131/136 is a truly revolutionary precision weapon, which challenges the West's defensive technologies and systems. - RUSI

Opening Salvo

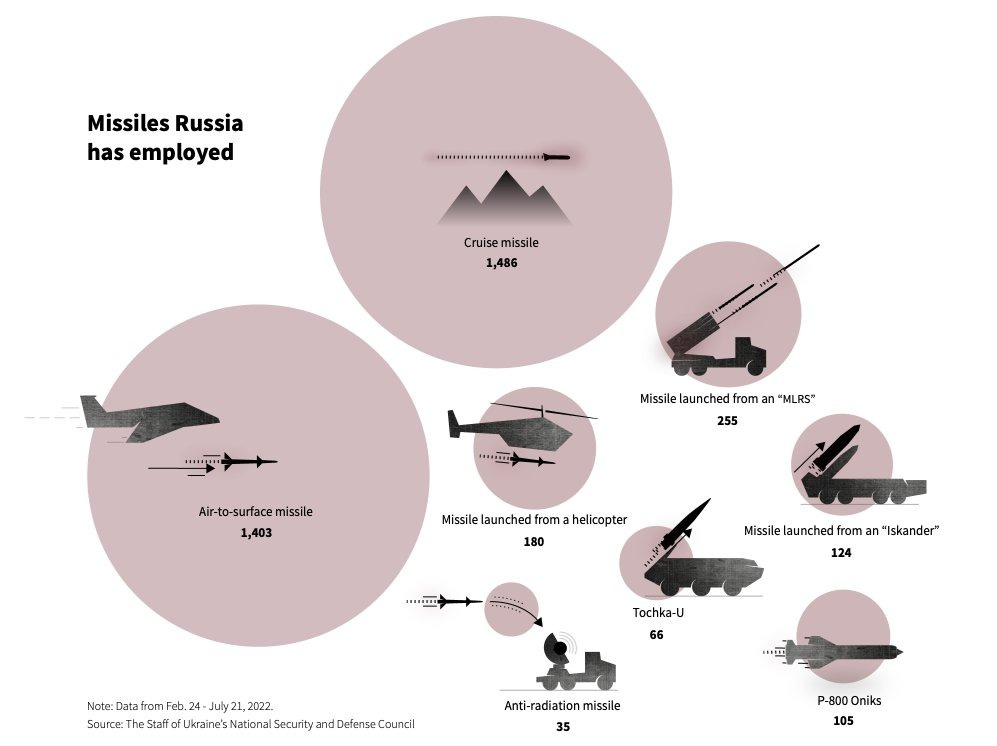

On October 10th, the Russians conducted a massive strike across the territory of Ukraine. 84 cruise missiles paired with 24 Geran-2s struck across 14 regions, damaging 30% of the country's energy infrastructure and plunging much of the country into a blackout. It was the largest single missile attack since the beginning of the conflict. While the AFU claimed 56 projectiles had been shot down, their air defenses had been overwhelmed. Over the course of the next week, similar strike packages of missiles and drones continued. By October 17th, over 400 projectiles had been launched in the new campaign. In visually censored videos posted by Ukrainians to Telegram, the now infamous "lawnmower" sound of the Geran-2's two-stroke piston engine was ever-present.

The following days and weeks would see steady waves of missile and drone attacks of an intensity not seen since the conflict’s opening days. According to reports from the UAF, Russia fired over 600 air- and sealaunched cruise missiles between October 10 and the end of 2022, with an average salvo size of around 50 missiles. Interspersed with these cruise missile attacks have been waves of one-way attack drones, primarily Shahed-136s, of which Ukraine says Russia launched nearly 700 between September 2022 and early January 2023. In mid-December, the United Nations assessed that Russia’s bombardment had damaged around 50 percent of Ukraine’s power grid. - CSIS

The Russians appeared to have stockpiled several hundred cruise missiles for the initial wave of attacks, and Western analysts hoped that they would soon exhaust their reserves. Instead, the attacks continued at a pace which – while reduced from the first week – demonstrated greater production capability than was thought to be possible. The Russian military-industrial complex had ramped up faster than expected, and the addition of the Geran meant that each missile launched was much more likely to find its target.

It was typical for the AFU to claim interception rates between 40-80%. Disregarding Russian MoD reports, Western analysts recognized that the censorship regime in place in Ukraine made verifying these reports "impossible" but tended to take them at face value. Some noticed that – contrary to common sense – the AFU was claiming that their interception rate was increasing as the Russians launched larger and more frequent attacks. While they claimed a roughly 10% interception rate for cruise missiles from February to July, by December, they were claiming to have shot down 80% on average. Was this the result of increased operator skill? Strategic changes in coverage? Perhaps the small number of NASAMS, IRIS-T, and Gepard systems delivered by the West were simply so effective they could be responsible. In November, US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin claimed the NASAMS had intercepted 100% of the cruise missiles it had attempted to hit.

Blackout

It seemed implausible to some that interception rates could increase by 800% at the same time that the Russians had begun firing much larger salvos, with a frequency that would allow them to quickly gather the deployment locations of the Ukrainian air defense network. It was also hard to reconcile with the constant and very public admissions by the Ukrainians of the damage the strikes were doing. With the exodus of civilians from the country and the loss of territory, the country's energy consumption was down 35%, and Ukraine's largely Soviet built grid provided overcapacity prior to the war and allowed the country to export significant amounts of electricity. But by January, Surovikin's campaign had left Ukrenergo and DTEK unable to meet a third of Ukraine's electrical needs. The key component that needed replacing was high-power transformers.

What went largely unstated in the media was that the Russian missile campaign had mostly targeted transformers and transmission lines rather than actual energy generation infrastructure like power plants. In the first months of strikes, hundreds of smaller 110 and 330 kV substations were targeted. In December, 750 kV stations – of which Ukraine had approximately ten – began to be targeted. This is the reverse order of what one would expect if permanently destroying the grid was the goal, so it seemed that the Russians were deliberately ratcheting up the pressure over time.

Earlier, nuclear energy specialist Aleksey Anpilogov drew attention to the fact that the Ukrainian substations with the highest voltage – 750 kV – were becoming the target of Russian missile strikes. “Until now, Ukraine has boasted that these substations were not disabled, saying that missiles did not strike their targets. But the fact is that the previous missile strikes were sparing; they disabled 110 kV and 330 kV substations,” the analyst explained.

There are less than ten substations with a voltage of 750 kV in Ukraine. “But the failure of each of them is actually the loss of several regions at once, because it is these substations that are responsible for the transfer of electricity between regions.” - New Cold War, November 24 2022

The destruction of transformers was a serious issue that, left unresolved, would turn Ukraine's energy districts into "islands" disconnected from each other, making balancing the grid impossible. These critical pieces of equipment are necessary to step down high voltage transmission to substations, cost millions of dollars, and weigh hundreds of tons. The loss of coal from mines in the Donbass meant the Ukrainians had shut down some coal power plants prior to the war, giving them a reserve of spare parts, but that reserve was running out.

European transformers were built to step down 400 kV and 200 kV transmissions, so adapting their hardware to the Ukrainian grid was only theoretically possible. A global shortage of transformers had been a reality for a decade at least, resulting in energy companies hoarding them for their own needs. In the US, companies often waited in excess of two years to receive a new unit after ordering one. In the EU, the timeframe exceeded three years. Production of large transformers was consolidated in only a few countries, none of which were in the West. And even if the West could find the high voltage transformers Ukrenergo wanted – in early January, they said they needed at least 59 – they would have to be delivered by ship because of their incredible size and weight. In November and January, the US and EU dispersed hundreds of millions of dollars meant to help the Ukrainians acquire more transformers, but this was significantly less than the Ukrainians would need, and just because they had cash didn't mean they could buy the equipment.

Ukraine's domestic transformer manufacturer, Zaporozhtransformator (ZTR) – once the largest in Europe – had been failing for years prior to the war. Industry experts said that the Ukrainian government had preferred to buy transformers from foreign countries using Western loan programs, resulting in ZTR consistently losing out in bidding processes. Its employee count dwindled steadily over the years, and it entered bankruptcy proceedings in 2019. The concern was partially owned by Russian oligarch Konstantin Grigorshin, so the Ukrainian government shut it down in March of 2022 and then attempted to nationalize it in November. A few weeks later, in early December, the company's production lines and warehouses in Zaporozhye were destroyed in a Russian missile strike.

Ironically, the country most capable of supplying transformers compatible with the Ukrainian grid was Russia itself, and this may have been the implicit threat of the missile campaign. The Russians had mostly refrained from destroying power plants, so the Ukrainian grid could conceivably be repaired in a matter of weeks if only replacement parts were available. If the Ukrainians failed to negotiate with the Russians, it could be years before their grid would be capable of meeting the country's energy demand, even if the missile strikes stopped entirely. Electricity imports from neighboring countries still depended on these transformers, so there wasn't much that Ukraine's partners could do.

Ukrenergo was forced to implement rolling blackouts throughout the country. A massive strike in the last week of November plunged the entire country into an hours-long blackout, demonstrating that a total system collapse was theoretically possible.

In March of 2023, the Ukrainian Air Force admitted it was not capable of shooting down the Iskander-M.

"We don’t shoot down ballistic missiles, for example Iskander-M. All these missiles fly fast, along a ballistic trajectory and essentially swoop down on a target with a huge speed. It takes specialized air defense missile systems to shoot down something that’s already falling." - PS ZSU spokesman Yury Ignat, March 2023 (TASS)

The Ukrainians desperately needed a game changer.

The Hype

Calls for the West to deliver Patriot batteries to Ukraine increased in proportion to the Russian strategic missile campaign against Ukraine's energy infrastructure. In mid-December, the Western media reported that the Biden administration was "considering" the delivery of at least one battery. Zelensky personally called President Biden on the 19th of December to urge him to send the system immediately. The next day, the decision had been made: Ukraine would be receiving a Patriot system. 100 Ukrainian soldiers – enough to operate a single battery – flew to Fort Sill, Oklahoma to start training.

Reacting to the news that the U.S. is likely to supply Patriot air defense missile systems to Ukraine, a senior Ukrainian Defense official told ABC News that they will be "a game changer," describing them as "one of the best systems in the world". The official added that Ukraine's access to the missiles will "drastically increase our capacity to defend our skies from Russian strikes." - ABC News, December 14 2022

The Patriot (a backronym for "Phased Array Tracking Radar for Intercept on Target") was developed as a replacement for the Nike Hercules missile system and was first deployed in the closing phase of the Cold War. It proved its efficacy during the Gulf War, during which the American military claimed an astonishing nearly 100% interception rate against Soviet SCUD ballistic missiles – the Iskander's predecessor's predecessor – launched by Iraq. Its performance was so noteworthy that President George H.W. Bush specifically mentioned the interception rate, saying "Patriot is 41 for 42: 42 Scuds engaged, 41 intercepted!" during a public statement at a visit to the Raytheon plant in Massachusetts in February of 1991. Prior to the Gulf War, it was thought that ballistic missile interception was so difficult that shooting down even a sizeable minority of projectiles would prove impossible. Small-scale combat use of ballistic missiles had been limited to exchanges between minor powers without access to missile-based air defense systems, and the Patriot's success – the first real test of modern missile defense – marked a major shift in the history of warfare.

“The battlefield success of the Patriot and THAAD systems is undeniable. These are truly game-changing weapons.” - David B. Des Roches, Middle East Institute

By 2022, various iterations of the Patriot were in service with 17 countries, and the US alone fielded over 1,000 launchers. The Saudis used them to shoot down "hundreds" of projectiles fired at the country during its conflict in Yemen. "Everybody wants them," wrote analyst David B. Des Roches in August of 2022.

Concerns about the lengthy training process – up to a year for more technical roles in a Patriot battalion – were mitigated by some commenters. The Ukrainians would need some months of practice, but American training was excessive anyway:

“The complexity of training Ukrainians to use Patriot is overblown. Western training is massively over-engineered for health and safety purposes. It’s not uncommon to have to achieve a thousand hits in a simulator before you’re allowed to fire a live system. Russia can train a tank driver in four hours, while we spend four weeks." - Express

The Patriot, unlike Ukraine's aging S-300s, was "sophisticated" and among the most advanced air defense systems in the world, analysts said. It offered "increased accuracy" and "increased kill rate," and "does exactly what you want it to do." Its systems were "nearly autonomous," requiring only a final launch decision from operators. It could "intercept any aerial threat" under "any weather conditions." The Economist suggested that the Patriot may even be capable of shooting down Russian missiles like the Kh-22/32, which travel in excess of Mach 4.

White House, Pentagon and State Department officials declined to comment on details of the transfer of a Patriot battery, which, if approved, would amount to one of the most sophisticated weapons the United States has provided Ukraine. The Patriot system can knock down Russia’s ballistic missiles, unlike other systems the West has provided, and can hit targets much farther away - New York Times, December 13, 2022

In March, the New York Times reported that the Ukrainians at Fort Sill were nearly done with their 10-week crash course on the Patriot. Despite this period being a tiny fraction of the year required to typically train a Patriot battalion, the Ukrainians had already "mastered" the sophisticated system and were "essentially running their own training." They were even offering pointers to their American instructors, drawing from their – at this point – much more extensive combat experience. The Americans were impressed by how the Ukrainians had "breezed through" the training and called them "quick studies." The first battery was due to be deployed as early as April. Germany soon offered to provide one of their batteries as well.

On May 4th, 2023, Ukrainian social media reported that the newly deployed Patriot battery had done the impossible by shooting down a hypersonic Kh-47 Kinzhal. While Ukrainian Air Force spokesman Yuri Ignat initially denied that a Kinzhal had even been fired on the 4th, the branch's commander, Mykola Oleschuk, officially confirmed the shootdown two days later. His claim was validated by the Pentagon, and photographic proof of the missile – with a sizable interceptor fragment hole blasted through its nosecone – appeared shortly later. The Patriot had proved itself again.

The Reality

Two weeks later, on May 16th, a large Russian missile barrage struck the Kiev region. The next day, the Ukrainian Air Force claimed they had shot down a staggering 6 Kinzhals during the attack. If one Kinzhal had been perceived as impossible, six strained credulity. The Russians hadn't launched such a large number of them at once previously in the conflict. Shortly afterward, a webcam video recorded close to the Zhulyany airport in Kiev emerged on social media:

The AD launches seen in the video were universally accepted as belonging to a Patriot system because of their trademark 38 degree launch angle (other systems like the Iris-T and S-300 fire straight up into the air). Interceptor debris posted to social media showed that the missiles used were PAC-3 CRI, which are fired from the 16-missile variant of the Patriot launcher. With the 32 launches caught in the video, this meant that two launchers had likely fired their entire magazines. At $3 million per interceptor, a jaw-dropping $96 million of munitions had been expended in the span of a few minutes. Also, as shown in the video, multiple interceptor launches appear to have failed, with two falling to the ground and others suffering malfunctions that caused them to go off course.

Even worse, video from the same feed taken minutes later showed two large explosions in the vicinity of the launch locations (0:33 and 0:42 seconds in the video above) and possible secondary explosions shortly afterward, followed by large plumes of smoke. The Russian Ministry of Defense quickly reported that the Ukrainian claim of six Kinzhal shootdowns was impossible, as they hadn't even fired that many, and that they had destroyed five Patriot launchers and the radar station of the battery. Russian sources on Telegram said the Russians had baited the Patriot operators into turning on their radars with a wave of Geran-2s, then targeted those radars with Kh-31P anti-radiation missiles before finally targeting the launchers themselves with Kinzhals.

American media confirmed that one Patriot battery had been damaged on the 16th but denied the damage had been catastrophic. Rumors swirled on Telegram that the US military had proactively placed a moratorium on the Patriot's use in Ukraine until an investigation could be completed. Simultaneously, the SBU began a wave of arrests of Ukrainian citizens who had disseminated videos of the Patriot's operation and began taking street camera feeds offline.

"Such cameras work all over the world, broadcast online on Youtube channels. But in our situation, when there is martial law in the country, I think that certain adjustments will be made with the military administrations. When there is an air defense operation, when there is a threat of information leakage, I think that the bodies of military administrations will adjust in order to somehow prevent the enemy from being able to observe the combat operation of our air defense systems online." - Ukrainian Air Force spokesman Yuri Ignat

Additionally, with the photos of fallen interceptors having already been shared on social media, the idea that the Patriot had shot down a Kinzhal two weeks earlier became suspect. The nosecone of the missile in the photos appeared to have been hit by a fragmentation-type interceptor rather than a "hit to kill" type interceptor like the Pac-3 CSI the Ukrainians had clearly been given. Moreover, the "Kinzhal" in the photos the AFU provided was dramatically smaller than the actual missile and appeared to better match the dimensions of a BETAB-500 or P-800 Oniks. Some commentators posted speculative diagrams of the internals of the Kinzhal, and suggested perhaps the debris was from the missile's warhead or "penetrator," or even that a BETAB-500 had been embedded in the Kinzhal. In the ensuing online debate, it was hard to know what to believe.

The Hidden History

What wasn't surprising was that the Patriot in Kiev had failed to protect itself. Despite sometimes glowing reports about the system in the Western press, some commentators had issued warnings that the Patriot had serious limitations. Its last-generation radar, which the Ukrainians had received, does not provide 360-degree coverage like some other AD systems. In a battle space in which the Russians routinely sent missiles in weaving, looping patterns through the country to strike targets from behind, this meant the Patriot needed to be deployed along with significant quantities of other AD assets in a "layered" network. But with stockpiles of S-300, NASAM, and short-range interceptors being close to exhaustion, the Patriot couldn't depend on Western-grade supporting defenses.

The possible malfunctions seen in the May 16th video were similar to those seen in videos of the Patriot's operations in Saudi Arabia. Its interceptors had a proclivity for suddenly veering wildly off course before crashing into the ground. With Ukraine's batteries deployed in densely populated Kiev, this was dangerous.

Contrary to the statements of some analysts, the Patriot's history of "battlefield successes" was not undeniable and had been publicly and repeatedly challenged by both academics and analysts. The first Patriot interception claimed by US military officials – widely celebrated in the Western press – on January 18th, 1991, was later revealed to be "a computer glitch." No missiles had been fired at all. A Scud penetrated Patriot-guarded airspace in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia in late February of that year, killing 28 American soldiers in their barracks. Again, this was blamed on a computer glitch.

MIT professor and Pentagon consultant Theodore Postol became a particularly troubling thorn in the side of Raytheon, as he released analytical papers and gave congressional testimony that the Patriot may have shot down a total of zero Scuds during the Gulf War. Basing his analysis on debris photographs and videotapes taken by the US Army, Postol placed an upper bound on interception rates at 10%. He unwittingly stumbled into a complex political game. The Saudis, like the Ukrainians, had imposed a strict censorship regime over public reporting on failed Patriot interceptions in cooperation with the US military. The Israelis, who also depended on the Patriots to protect their territory from Iraqi Scuds, had no such restriction and openly validated Postol's analysis. While the IDF would acquire several Patriots over the following years, they expressed "dissatisfaction" with the system and prioritized the development of domestic alternatives. They have plans to mothball all of their Patriot batteries, and have rejected the idea of acquiring more.

Meanwhile, Peter Zimmerman of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, or CSIS, testified that Postol's analysis contained numerous methodological flaws. The CSIS is funded by both Raytheon, the Patriot's manufacturer, and the US government, and is cited extensively in earlier sections of this article. Congress did not find Zimmerman's testimony convincing, and released a summary of a report which contained the following passage:

"The Patriot missile system was not the spectacular success in the Persian Gulf War that the American public was led to believe. There is little evidence to prove that the Patriot hit more than a few Scud missiles launched by Iraq during the Gulf War, and there are some doubts about even these engagements. The public and the United States Congress were misled by definitive statements of success issued by administration and Raytheon representatives during and after the war."

Lobbying by the US Army and Raytheon ensured the full report was never released to the public.

Just as in the Gulf War, official US military reports on the Patriot's performance in the 2003 invasion of Iraq were highly positive. Several troubling incidents occurred, however. Two British pilots were killed when their Tornado was shot down by a Patriot in March of 2003, and an American F-18 pilot was killed similarly in April. Also in March, a USAF F-16CJ conducting SEAD detected a lock on from a friendly Patriot radar and mistook it for an Iraqi SAM. The pilot fired a HARM anti-radiation missile at the battery, which failed to defend itself, resulting in the destruction of its radar array.

Even with the Saudis and Raytheon continuing to run interference for the Patriot's shortcomings, Saudi reliance on the system and participation in regional conflicts meant that hiding its performance record was a losing battle. After the Riyadh attack in March of 2018, Foreign Policy published a scathing article titled "Patriot Missiles Are Made in America and Fail Everywhere." In the piece, FP described the Patriot as "a lemon," and publicly challenged Saudi/US reports on Patriot interceptions:

On March 25, Houthi forces in Yemen fired seven missiles at Riyadh. Saudi Arabia confirmed the launches and asserted that it successfully intercepted all seven. This wasn’t true. It’s not just that falling debris in Riyadh killed at least one person and sent two more to the hospital. There’s no evidence that Saudi Arabia intercepted any missiles at all. And that raises uncomfortable questions not just about the Saudis, but about the United States, which seems to have sold them — and its own public — a lemon of a missile defense system.

The author, Jeffrey Lewis, and other analysts at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies conducted detailed reviews of prior attacks in 2017. In each case, they saw no evidence that Saudi claims of shootdowns were true. They accused the Saudis of using discarded missile airframes, which often separate from a missile's warhead in flight, as evidence of a shootdown. Meanwhile, photographs of damage caused by the warheads hundreds of meters away from the debris had slipped through to the public. Lewis said there was no reason to think that that interception had even been attempted in the first 2017 attack, or that the Saudi Patriots had intercepted a single Houthi missile over the course of their conflict with the Houthis. After examining now-declassified Gulf War documents, he said there was no evidence that the Patriot had ever intercepted a ballistic missile.

In 2019, at least one KSA Patriot battalion failed during a large attack on Saudi oil processing facilities by Ansar Allah. The attack was devastating, temporarily cutting Saudi oil production in half and reducing global oil production by 5%. The Houthis claimed only ten drones had been used in the attack, but the Saudis contradicted this by saying Iranian cruise missiles had been used as well. The incident ignited a media firestorm, with various countries variously naming the Iranians the Houthis, or both as the responsible party. A rift formed between the Saudis and Americans as a result. The economic results were severe, triggering huge surges and declines in various global markets, delaying the long-planned IPO of Saudi Aramco, and causing the Americans to conduct an emergency release of the US Strategic Petroleum Reserve to stabilize prices. During talks in Ankara, Vladimir Putin offered to sell the Saudis the Russian S-400 system as a replacement for the Patriot while Iranian President Hassan Rouhani chuckled beside him.

Foreshadowing the Patriot's failures in Ukraine, conflicting reports made it difficult to make sense of the incident. Had cruise missiles been used? Which direction had they come from? The Patriot battery stationed at Abqaiq-Khurais was backed up, as designed, by other layers of air defense, including Skyguard AA guns and French Shahine short-range missile systems. Yet, neither the Patriot nor the Shahines had detected a single drone on radar or launched a single interceptor. Just as would happen in Ukraine a few years later, the installation's guards were left to fire wildly at the incoming projectiles with small arms. If one of the poorest political forces in the world – regardless of whether they had Iranian help or not – could penetrate a layered, modern air defense system, the implications were massive.

Jeffrey Lewis understood these implications in 2018. In his FP piece, he offered an explanation for how the Patriot – one of the most expensive military systems ever made – could sell so well while being so ineffective. It's worth quoting this passage in full:

If the Patriot system doesn’t work, why would the United States or the Saudi government claim otherwise? At some level, we should be sympathetic. The basic function of a government is to provide security for its citizens. There is enormous pressure on the Saudi government to show that it is taking steps to defend its citizens. By asserting successful intercepts — assertions that are uncritically spread in headlines — the Saudi government is able to present itself as fulfilling its obligations to protect its population. And, like in 1991, the perception that a defense is working helps keep a lid on regional tensions. Just as false claims about missile defenses helped keep Israel from retaliating against Iraq during the 1991 Gulf War, perhaps the fable that Riyadh is defended makes it easier to ignore the fact that Iranian proxies are firing Iranian missiles into Saudi Arabia’s capital.

But my colleagues and I are independent analysts, not government functionaries. Our obligation is to the truth — and in this case, the truth seems to be that these systems are not working. The danger here is that leaders in Saudi Arabia and the United States will come to believe their own nonsense. Consider this: Despite that the fact that anonymous U.S. officials have confirmed that there was no successful intercept in November 2017, President Donald Trump had a very different impression: “Our system knocked the missile out of the air,” Trump told reporters the following day. “That’s how good we are. Nobody makes what we make, and now we’re selling it all over the world.” This is a theme Trump has returned to again and again. When asked about the threat from North Korea’s nuclear-armed missiles, Trump said, “We have missiles that can knock out a missile in the air 97 percent of the time, and if you send two of them, it’s going to get knocked down.” Trump has repeatedly given every indication that he believes missile defenses will protect the United States.

It is no surprise, then, that the long history of obfuscation and deception related to the Patriot's capabilities would continue during the war in Ukraine. Two weeks after claiming their seventh Kinzhal shootdown, President Zelensky claimed that the Patriot would ensure a "100% interception rate" of "any" Russian missile after a daylight attack on May 29th. The Ukrainian Air Force said that this attack had included Iskander-M quasi-ballistic missiles and implied Ukraine's Patriots – presumably some components of which were out of action for repairs – had shot them down. But given what we know about the Patriot's track record, is this plausible? The Iskander-M is significantly more advanced than Houthi missiles or Soviet-era Scuds the Patriot had previously failed to intercept, as it maneuvers dramatically during flight, and drops decoys. How could Ukraine's two Patriot batteries, and not even full batteries at that, do what Saudi and American systems couldn't, given the AFU's truncated training time and lack of other modern layers of air defense?

In a series of admissions across late 2023 and 2024, the AFU gradually disclosed the realities on the ground and in the air over Ukraine, sometimes contradicting previous claims. They had failed to intercept a single Kh-22 or Kh-32 cruise missile since the beginning of the war. Their S-300s were completely incapable of intercepting the Kinzhal, Iskander, or Oniks. In August of 2024, AFU commander Syrsky published a list of interception rates for various Russian projectiles. Whether the report told the whole story or not, it made some surprising admissions. Over the course of the war, the Ukrainians had only intercepted 25% of incoming missiles. Ballistic missiles like the Iskander had been intercepted at a 4.5% rate, and the Oniks at 5%. Implausibly, the report still claimed that 25% of Kinzhals had been intercepted, and two of six rare Zircon hypersonics had been shot down. Why the slower Iskander-M was harder to shoot down than the much faster Kinzhal was not explained, and in January of 2024, the AFU claimed to have downed 10 Kinzhals in a single day – a 100% interception rate.

As the need for more air defense systems and larger deliveries of interceptors became increasingly dire, the Ukrainians revised their once-high interception rates lower and lower. By March of 2024, their monthly claimed interception rate dropped below 50% for the first time since they received Patriots.

Even if the Patriot was as effective as initially claimed, the introduction of the Geran platform dramatically tilted the balance of the missile attrition war even further toward the Russian side. The Russians quickly began to manufacture them domestically and set production targets in the thousands annually. While the drone could be engaged with anti-aircraft guns, the short range of those systems and the quantity of Gerans used in strikes meant that interceptor missiles would need to be expended to combat them. Interceptors are sophisticated – their task could be compared to needing to shoot a bullet out of the air with another bullet – and range from ten to over one hundred times the cost of a Geran-2. Even worse, the Geran's tiny heat and radar signatures make it a very difficult target to hit, potentially requiring multiple interceptors. Successful shootdowns with AA guns became much harder to achieve as daytime attacks dwindled, night attacks increased, and videos of failed missile interceptions were posted. On a long enough timeline, even if Ukraine's Western partners ramped up interceptor production, the procurement math simply didn't work out. With global production of Patriot interceptors unlikely to break more than a few hundred a year, there was no way out of the problem.

Meanwhile, Russian missile production had kicked into full gear, and two years of strikes had given them a chance to master tactics. Mixed strike packages of drones and cruise missiles increasingly contained Iskander-Ms. Maps of missile flight paths became complex. Initial waves of projectiles probed for gaps in air defense, ensuring subsequent projectiles would make it through. The Ukrainian Air Force said that some Russian missiles were inexplicably capable of suddenly "becoming invisible" during parts of their flight path. The Ukrainians were forced to severely ration interceptors and began to report running out of them midway through Russian strikes. Russian reconnaissance UAVs began operating behind Ukrainian lines, unthreatened by air defense. A clear video of a Kinzhal strike finally emerged, showing the missile body glowing red hot, which suggested it was perhaps just as fast in its burnout phase as the Russians claimed, and likely impossible to intercept after all.

Russian attacks on the Ukrainian energy grid have continued. By the fall of 2024, more than half of Ukrainian electrical production capacity has been destroyed. Increased Russian ISR capability has allowed devastating strikes on concentrations of foreign fighters and key weapons systems – including a second Patriot battery at least partially destroyed by an Iskander during transport in the spring of 2024. Russian reports said that Iskander production rates had reached a level where the platform could be transferred to the control of lower level commanders closer to the front line – rather than in centralized missile units – shortening response times. Rumors of secret truces between the Russians and Ukrainians to reduce attacks on each other's energy infrastructure have circulated, but on the 16th of November, the Russian military launched the largest strike of the war. It isn't clear if – or how long – Ukraine's grid can survive.

While Ukraine's Patriots have occasionally succeeded in downing Russian aircraft, the system's impact has been limited by its technical shortcomings, interceptor shortages, and its vulnerability to an adversary with superior strike capabilities.

Patriot Games

In October of 2024, Iran unleashed a massive ballistic missile strike on Israeli military targets. The results of this strike have been just as muddled and confused as every previous high-profile air defense engagement in modern war. What was not muddled, however, was the enormous quantity of crystal clear videos of dozens of ballistic missiles penetrating Israeli air defenses. The Israelis had long considered the Patriot insufficient for their needs, and their domestic systems enjoyed a sterling reputation after years of successfully shooting down garage-made unguided rockets fired by Hamas. But these defenses had failed, and done so indisputably. Subsequent attacks from Hezbollah featuring much smaller salvos of less than 10 ballistic missiles – and less sophisticated ones than the Iranians had used – also penetrated the Israeli missile shield. Even the Russians – perhaps the other contender for the country with the most advanced air defense systems besides Israel – had suffered several major penetrations through the course of the Ukraine war. Sure, the Russians had a much larger area to cover than the Israelis did, but by the end of 2024, the public at large had incomparably more evidence than it had ever had before that the entire concept of missile defense was just as suspect as analysts believed it was prior to the Gulf War. The games of public relations and propaganda surrounding not just the Patriot but air defense in general, could end.

It is likely the case that Patriot is inferior to its counterparts in service with the IDF and the Russian Armed Forces. But regardless of the variance in efficacy, the Russians, Iranians, and Houthis have conclusively demonstrated in the span of a few years that a massive asymmetry exists in modern warfare. Forces with few resources can attack much more powerful forces at will. Nations that have prioritized developing deep stockpiles of advanced missiles and simple drones are at a massive advantage. An objective observer has no choice but to acknowledge that strategic thinking – at least as portrayed to the public – is deeply flawed. The populations of major military powers have been manipulated for decades to believe that their safety can be assured, but this is not the case. It is not an exaggeration to say that the only thing that prevents precision strikes on nearly any target in the world is the collective cool heads of the commanders and politicians who choose daily not to press the button. It could also be said that the best defense is, as always, a good offense. Regardless, it's past time to admit the truth. Returning to Lewis:

Missile defense systems do not represent a solution to the challenge posed by growing missile capabilities or an escape from vulnerability in the nuclear age. There is no magic wand that can “knock down” all the missiles aimed at the United States or its allies. The only solution is to persuade countries not to build these weapons in the first place. If we fail, defenses won’t save us.

Game Changer Rating: 2/10

Thank you to @_Kinez_ for assistance in researching Ukrainian energy infrastructure

I tend to think that the most important 'game changing' weapon system that the west has introduced in the Ukrainian theatre is the one that has gotten the least publicity - and that is starlink.

The largest advantage the west has is the vast network of isr - both commercial & military - that the west can concentrate & leverage in any situation.

Russian ECM seems to have neutralised much of it as regards to weapon system use - as you pointed out, blocking out GPS has crippled many advanced western systems.

But starlink distributed closed networks are a problem - allowing the US/NATO to still leverage the massive scale of the ISR networks.

Starlink seems to be the big winner out of all systems introduced - and I think it will be the most important military system for the west going forward (as everything in the west now seems to revolve around processing power and the sheer amount of data).

And very little has been written about it.

I would be very interested in reading a good article on it.

Here is a few that go into it a bit - but nothing on Ukraine:

https://maxpolyakov.com/hidden-military-potential-of-starlink/

https://interpret.csis.org/translations/the-u-s-starlink-project-and-its-implications-from-the-perspective-of-international-and-national-security/

https://lieber.westpoint.edu/can-starlink-satellites-be-lawfully-targeted/

Anyway - good read.

Thanks for the analysis.

Ken

Great to see the "Game Changer Rating" is back.