Clusterf*ck

An Evaluation of Western Wunderwaffen in the Ukraine War (Part 6)

After covering both the 155 mm shell shortage in Part 2 and the Ukrainian 2023 Summer Offensive in Part 4, in this part of the series we’ll be discussing how the two issues intersected to create one of the most divisive controversies of the war in Ukraine so far. While prior entries in this series showed that Western leaders were willing to contradict prior statements and promises as the war progressed, in the case of cluster munitions, they went a step further – violating their own established moral precedent and international law. In doing so, two major discoveries were revealed for the first time: the depth of the military production crisis in the West, and the depths to which US and EU officials would sink to ensure the war would continue. If this is your entry point to this series, you can start at the beginning below.

General Dynamics Dual-Purpose Improved Conventional Munition (DPICM)

First referred to as a game changer: July 2023

Appearance in Ukraine: July 2023

Country of origin: United States

Unit Cost: $0 (cost more to destroy than to send as aid)

Number sent: At least “hundreds of thousands,” as many as a few million

Manufacturer market cap: $89B

As Ukraine’s 2023 Summer Offensive stalled, dragging into the autumn of that year, AFU commanders went back to the drawing board. Their armored thrusts – designed by NATO trainers and composed of NATO equipment – had thus far been largely repulsed by the so-called Surovikin Line. For the Ukrainians, who lacked the air superiority required to soften up the Russian defenses with airstrikes, the only options available to them were artillery and drones. The problem, however, was that the Russians outgunned them. Severe shortages of both artillery pieces and ammunition meant that whatever damage they could inflict on the Russian defenses would be repaid many times over by their opponent’s guns.

Desperate attempts by Ukraine’s Western partners to scrounge up 155mm shells had only provided temporary stopgaps. US military production of shells – long hampered by a string of industrial debacles and controversies – was nowhere near what the Ukrainians needed. There was, however, a potential solution, but the world wasn’t going to like it.

The Department of Defense was in possession of a vast stockpile of long-expired artillery shells called “dual-purpose improved conventional munitions”, or DPICM. The public would be more likely to recognize them as the general term for warheads of their type: cluster munitions.

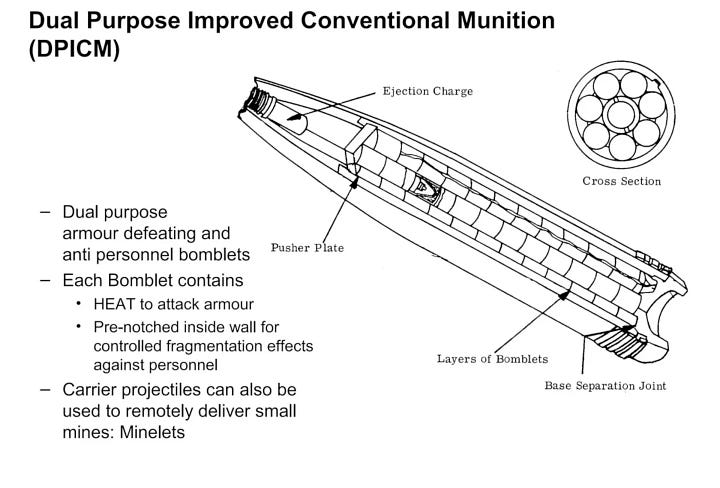

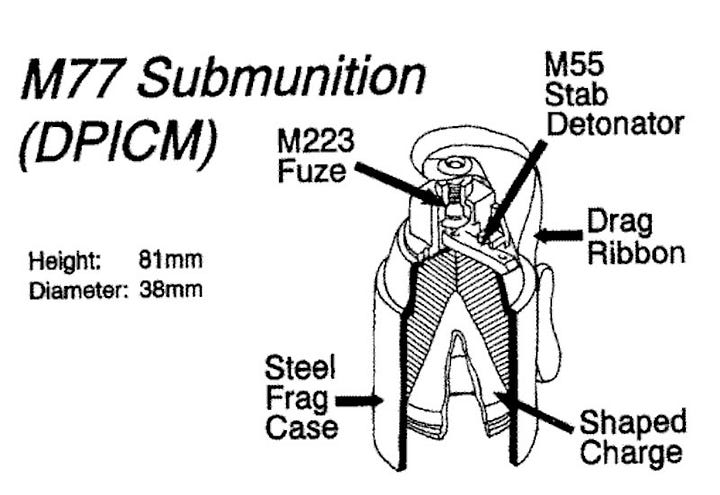

The DPICM is a broad category of warhead type that can be delivered by various platforms, from artillery shells, to unguided rockets, to guided missiles like the ATACMS. The base of the projectile is forcibly blown outwards in flight, while centrifugal force sends up to 180 bomblets flying outwards over a wide area. Depending on the model of warhead used, a cluster munition can spread its bomblets over an area as large as 57 acres. The “dual” in “dual-purpose” indicates the evolution from the warhead’s predecessor, the ICM, which was filled with simple anti-personnel grenades. The DPICM features a shaped charge beneath the fragmentary casing to provide some (limited) capability against hard targets, like armored vehicles.

While cluster munitions were first developed during World War 2, their use exploded during the Vietnam War, where they accounted for the outright majority of munition types dropped by the USAF. 260 million bomblets were dispersed over Vietnam alone between 1964 and 1973, with a staggering failure rate of 30%, leaving 80 million grenade-size bombs hanging in trees, sitting on rooftops, and lying in wait under grass.

Duds are more or less inherent in the production of cheap cluster munitions; the small mass of the bomblets means a lower touchdown speed, so impact fuzes are less reliable. A typical cluster munition has anywhere from 40 to 200 fuzes total, greatly increasing the likelihood of failures. And self-destruct mechanisms and complex sensors are cost-prohibitive, especially in a conflict where hundreds of millions of bomblets are being produced, like Vietnam.

Tens of thousands of civilians in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia have been killed by Vietnam War era DPICM/ICM duds. Hundreds of millions of dollars have been spent (including by the US) to find and destroy the millions of them still littering the countryside, but munitions experts estimate it could take another century to declare the region clear.

Three years after the end of the Vietnam War, US President Jimmy Carter broke the legal agreement between the US and Israel limiting military aid to defensive purposes by sending DPICMs to Israel, which then used them to bomb Lebanon during the first Israeli invasion of its northern neighbor. The dud rate for these munitions was even worse than Vietnam, leaving over a million unexploded bomblets on the ground by the end of the Israeli-Hezbollah war. In the last three days of the 2006 war – after a ceasefire had already been agreed – the IDF fired four million bomblets into Lebanon as a parting gift.

The story has been the same across dozens of conflicts since the proliferation of the munition type, with widespread use in the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia, the Gulf and Iraq wars, the Western Sahara War (1975-1991), the Nogorno-Karabakh conflicts, and the Soviet-Afghan War. In each case, civilian casualties due to cluster munition use were high.

The dire situation in Lebanon and decades of advocacy by humanitarian groups built up enough pressure to force the governments of the world to take action, culminating in the Convention on Cluster Munitions being signed by 94 states in Dublin in 2008. The treaty’s restrictions were total – banning not just the use of cluster munitions, but the development, production, stockpiling, or transfer of them, in addition to rendering assistance to a third party in doing any of the above. Notable non-signatories included the US, Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Finland, Israel, and China. Two years before the CCM was signed, a bill in the US Senate limiting the use of cluster munitions was defeated by a strong majority, which included Hillary Clinton. In 2010, the Obama-era Pentagon argued that cluster munitions actually cause less harm to civilians than “some other types of weapons.” Which weapons they may have been referring to I’ll leave to the reader’s imagination.

Nevertheless, the Department of Defense greatly reduced its use of cluster munitions by the mid 2000s. New targets were set to eliminate the procurement of cluster munition types with dud rates in excess of 1%. Development of GMLRS cluster rockets ceased in 2008 because their failure rate exceeded this margin by at least five times. The deadline for a long-planned self-imposed ban supposed to take effect in 2018 was cancelled, as defense contractors were unable to create a cluster munition with failure rates under 1%.

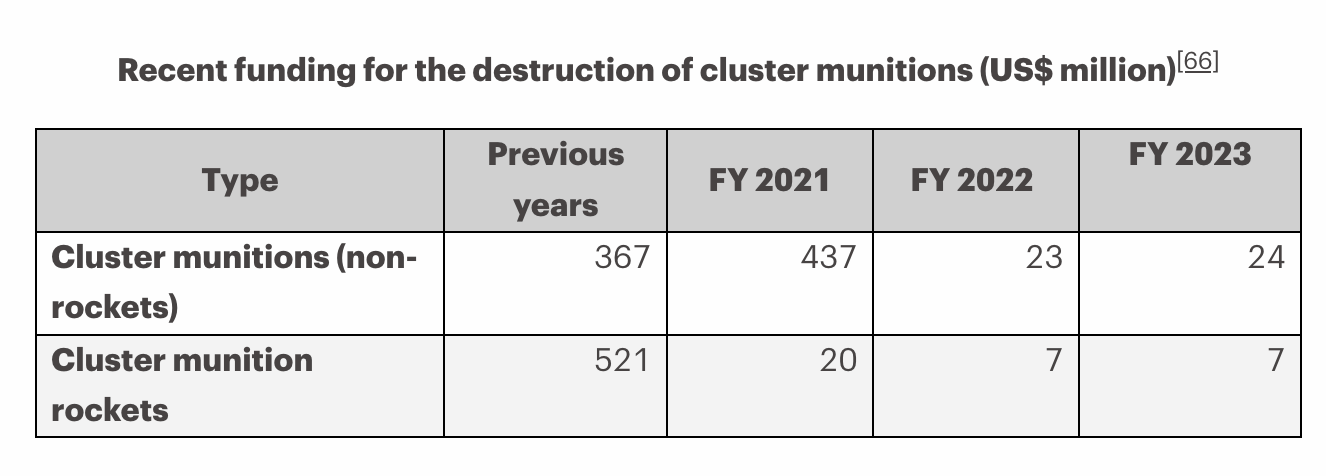

This left the Pentagon in a difficult situation. Cluster munitions were of limited use to them, due to the controversy, but the Army had millions of them – over 5.5 million of them to be exact, containing 728.5 million submunitions. Human Rights Watch estimated a billion submunitions were closer to the true total, because the DoD hadn’t counted what it had in the War Reserve Stock for Allies. 80% of the Army’s available tube and rocket artillery ammunition were cluster munitions. Cost intensive efforts to retrofit old warheads with self-destruct fuzes hadn’t made it far, because only .00004% of the DoD’s inventory in 2004 had been retrofitted, but Pentagon reports admitted that the retrofitting didn’t bring the dud rate under 1% anyway. 90% of the total stockpile was DPICMs, with the bulk of these rapidly approaching the end of their service life. Destroying the stockpile would be extraordinarily expensive, with estimates of tens of thousands or even a million dollars per ton, and the US stockpile contained hundreds of thousands of tons.

Just like with the massive, useless surplus stockpiles of the MRAP, the war in Ukraine presented the Pentagon with a potential win/win situation. It had deep stockpiles of aging weapons it had no use for, couldn’t sell, and couldn’t afford to destroy. The Ukrainians had a desperate shortage of 155mm artillery ammunition, and the barrels of their artillery pieces were being overused to the point of self-destruction. Cluster warheads don’t require a well maintained, accurate barrel because their area of effect can be measured in acres. As these twin needs intersected, the media and a collection of think tanks stepped up to resolve the only roadblock: public relations.

In the period before the Ukrainian 2023 summer offensive, discussion of cluster munitions in the media was almost exclusively limited to a single form: condemnation of their use by Russia.

Sporadic Russian use of Soviet-era cluster bombs and rockets was universally criticized in the mainstream press, and included in lengthy lists of alleged war crimes. The Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs joined in with the chorus, saying that the Russians were using them intentionally to increase civilian casualties.

The MFA [of Ukraine] emphasized that Russian forces deliberately use cluster munitions to maximize civilian casualties. This is part of their campaign of terror. (RBC-Ukraine)

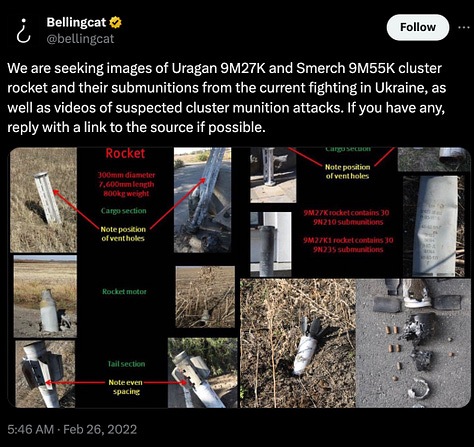

What went unsaid was that cluster munition use by both sides wasn’t new. The Ukrainians had a stock of aging Smerch and Uragan rockets with cluster warheads, and the Russian stocks were significantly larger, though they had newer models with lower dud rates as well. In 2014, Ukrainian government forces struck downtown Donetsk with cluster rockets repeatedly, killing a Red Cross worker and six others.

This history was largely ignored during the early stages of the 2022 invasion, as Russian cluster rockets killed civilians in several incidents. The Ukrainians fired back with cluster munitions of their own, hitting central Izyum while it was occupied by the Russian army in 2022, killing at least eight Ukrainian civilians:

The total number of civilians killed and wounded in the cluster munition attacks that Human Rights Watch examined is most likely greater. Russian forces took many injured civilians to Russia for medical care and many had not returned when Human Rights Watch visited. An ambulance driver said he and his colleagues had regularly transported and treated civilians, including children, with cluster munition injuries during the Russian occupation. He estimated that he took at least one such case to the hospital every day. (HRW)

While on the ground reports like the HRW one linked above occasionally cropped up, they made few headlines. The bulk of the media response singled out cluster munition use by the Russians. The EU and NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said the Russian cluster munition use was “a flagrant violation of international law.” Meanwhile, unbeknownst to the media, the Ukrainians were lobbying the Biden administration to urgently send DPICMs to Ukraine.

Ukrainian officials and lawmakers have in recent months urged the Biden administration and members of Congress to provide the Ukrainian military with cluster munition warheads, weapons that are banned by more than 100 countries but that Russia continues to use to devastating effect inside Ukraine.

The Ukrainian request for the cluster munitions, which was described to CNN by multiple US and Ukrainian officials, is one of the most controversial requests the Ukrainians have made to the US since the war began in February.

Senior Biden administration officials have been fielding this request for months and have not rejected it outright, CNN has learned, a detail that has not been previously reported. (CNN)

An explosive CNN report in December of 2022 brought the negotiations to light for the first time. In this report, the rationale for overriding an act of Congress, Pentagon policy, and the widely held Western moral framework was starting to take hold. A Ukrainian official was quoted saying, “So what, Russians use cluster munitions against us, the US worry is about collateral damage. We are going to use them against Russian troops, not against the Russian population.” (Note: the AFU would use cluster munitions – possibly DPICMs – in a strike on downtown Belgorod in December of 2023, killing 21, including three children, and wounding 110).

The Ukrainians argued that the Russians were using cluster munitions, and had killed civilians with them; therefore it was only right that surplus US cluster munitions should be given to the Ukrainians. This may seem like an exaggeration, but this was the logic:

Ukrainian officials, however, argue that the Russians are using cluster munitions extensively, and largely in civilian areas. For that reason, the Ukrainians have approached the State Department, Pentagon and Congress “many times” to lobby for the munitions, known as dual-purpose improved conventional munitions, multiple sources familiar with the lobbying effort told CNN.

Ukrainian lawmaker Oleksiy Goncharenko is among the officials who has been pushing the US to provide the munitions. “It is extremely important, first of all because it will really change the situation on the battlefield,” he told CNN. “With these, Ukraine will finish this war much faster, to the benefit of everybody. Russia is extensively using the old styles, the most barbaric styles, of cluster munitions against Ukraine,” Goncharenko added. “Personally, I was a victim of this. I was under this shelling. So we have all the right to use it against them.” (Emphasis mine)

The Biden administration said it wouldn’t transfer the shells and rockets unless “absolutely necessary” and that it didn’t believe the munitions were “imperative to Ukraine’s success on the battlefield.” Whatever the Ukrainians said their rationale was, they knew better – it was absolutely necessary, because they were running out of ammunition. The AFU would soon exhaust its supply of Soviet caliber 152mm shells sourced from ex-Warsaw Pact allies, and the available reserves of 155mm shells in NATO stocks were much too small to sustain the rate of fire they needed to keep up with the Russians. Efforts to ramp up 155mm shell production in the US, Germany, and elsewhere would still be too little, too late, and history would vindicate the Ukrainians for being skeptical of NATO’s ability to hit them.

All advocacy for the transfer beyond this simple point was fluff, and there was plenty of fluff in the months between the release of the CNN report and the Biden administration’s announcement that the Ukrainians would be receiving DPICMs.

“As we got in May 2022 155-millimeter artillery systems, it became a game changer. In July, we got different types of Multiple Launch Rocket Systems it became the next game changer … And I hope that cluster munitions become a next game changer as weaponry or ammunition for liberation of our temporarily occupied territories.” Oleksiy Rezinov, Ukrainian Defense Minister (Politico)

Ukrainian Defense Minister Oleksiy Reznikov said he hoped DPICMs would be a “game changer.” He promised the munitions would only be used against “non-urban areas.” Analysts cited Vietnam War era DoD reports that said cluster munitions achieved a much higher kill rate, bomb for bomb, than unitary warheads. President Zelensky said the request was “about justice” and he would limit the use of the weapons “purely to the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine.” Why it mattered whose territory they’d be used on, and why it was a good thing to litter Ukrainian territory that would presumably be reclaimed with unexploded ordinance, went unsaid.

Democratic Party representatives who had just months earlier demanded action from the Pentagon to limit cluster munitions use began to “soften” their stance. A collection of Congressmen sent a public letter to the Biden administration in March demanding the President overrule the law banning the export of cluster munitions with a failure rate higher than 1%.

The DPICM’s greatest advocate was Dan Rice, a US Army veteran and advisor to the Armed Forces of Ukraine officially registered under FARA as a foreign agent. Rice went on a press tour promoting cluster munitions, comparing them to firing “a flame thrower at a bunch of ants,” and calling them “five to ten times more lethal” than unitary artillery shells.

“This is how you increase the base lethality and win the war. If we want to win it, we need to give them something like that,” he told CNN, calling cluster bombs a “game changer.”

Rice took his advocacy for the cluster munitions to extreme heights, publicly calling for NATO as a whole to abandon the Cluster Munitions Convention, saying Europe “must break from the shackles of munitions laws.” He said the Europeans had become “seduced by the conceit” of their “own virtue” and “sanctimonious” with their “misguided” and “naive” ban on cluster munitions. He identified himself as Ukraine’s “chief advocate” for cluster munitions and called on Europe to begin manufacturing them immediately. Rice and other supporters of the move said DPICMs would end the war sooner, so any civilian deaths from their use would be made up for by a shorter war.

Rice was up against an enormous amount of opposition. Spanish, British, and German officials publicly condemned the transfer. A litany of human rights groups and a minority of US legislators issued public statements pleading with the President to reject the Ukrainian request. But in July, as the anticipation for the Ukrainian summer offensive reached a fever pitch, the Biden administration announced they had approved the transfer. Ukraine would soon join the very short list of countries to use cluster munitions on what it claimed to be its own territory.

The reaction was split. RUSI, which frequently appears in this series, said objections to cluster munitions use were “irrelevant” and “morally questionable.” RUSI borrowed the “Russia is doing it, so Ukraine can too” argument, saying it was “illogical” to claim more unexploded bomblets would add to the already existing problem:

HRW argues that because some DPICM submunitions will fail to explode, they are inherently indiscriminate. The problem with this argument is that a significant proportion of other munitions also fail to explode. In fact, up to one in five of Russia’s munitions stocks are assessed by the Russian military to be unsafe due to their age and poor condition, and yet these are routinely fired at Ukraine. HRW’s unexploded ordnance argument is one that would apply equally to a wide range of explosive weapons already in use in the conflict, and it is therefore illogical as a reason to specifically reject the provision of DPICMs. (RUSI)

RAND agreed, saying the shells could make the difference in Ukraine’s stalled offensive. The Wall Street Journal supported the transfer, while the New York Times did not. Advocacy groups like the International Campaign to Ban Landmines were outraged. More than two dozen world leaders condemned the move.

The Pentagon maintains the cluster munitions could help Ukraine advance and stop the Russian bombings. But Eric Eikenberry, the government relations director at Win Without War, countered the argument as “speculative.”

“We’ve already seen this in conflict,” Eikenberry said, dismissing “the idea that these are going to be a huge boon, the counteroffensive is going to jet forward and we’re going to save lives in the aggregate because these are going to be the wonder weapons that flip the battlefield in our favor and takes Russian artillery out of commission.”

Despite public statements of opposition from German officials like Annalena Baerbock, the Germans allowed the transfer of cluster munitions through German territory, breaking international law and violating the Convention on Cluster Munitions they had just claimed to still uphold.

The Pentagon assured the public that it would be sending DPICMs with low dud rates, around 3%. The quantities and specific models that have been transferred are classified, but all available evidence suggests that the true dud rate is as much as ten times higher, and the Pentagon has been repeatedly caught fudging the numbers.

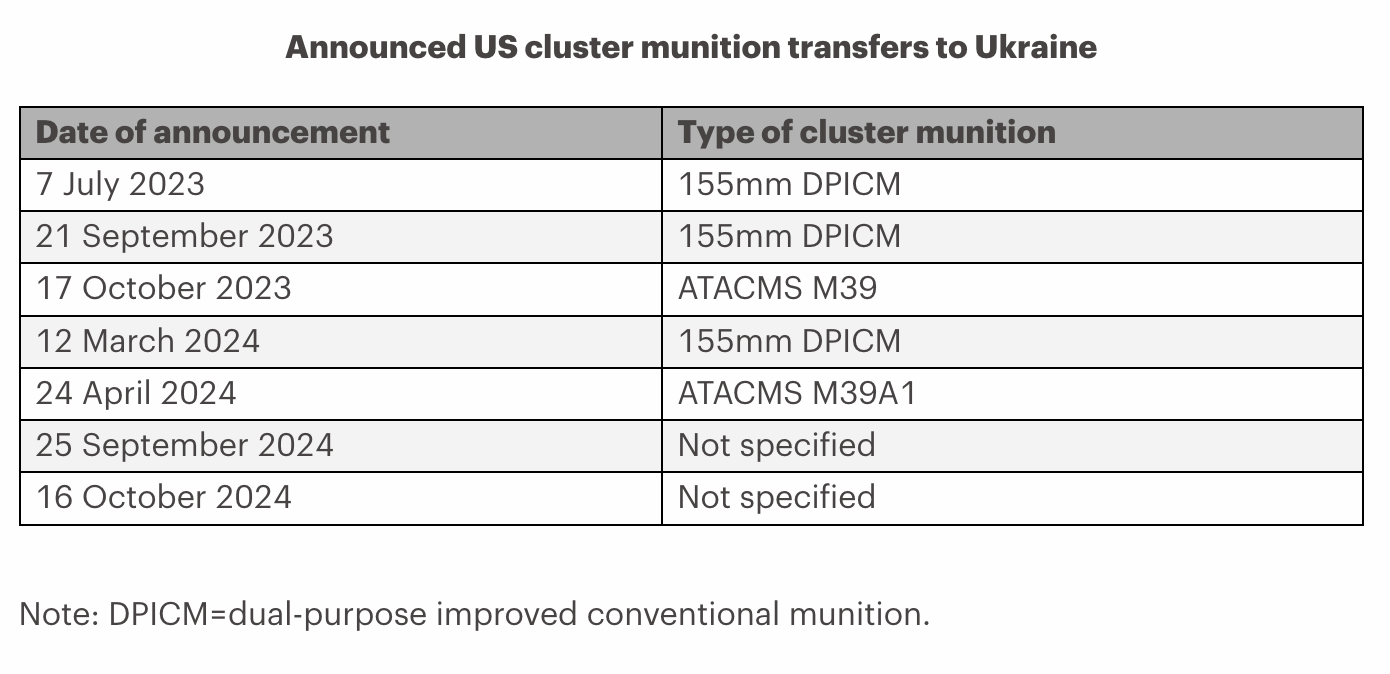

The hard reality of the situation is that the Ukrainians couldn’t afford to care about the dud rate anyway. They needed the entire US DPICM stockpile, and they needed it immediately. By 2023, the total number of 155mm cluster shells in the US inventory was likely under 3 million, after years and hundreds of millions of dollars had been spent reducing it by destroying shells. Three million shells would buy the Ukrainians a year of parity with the Russians, who were already producing that many annually – more than the US and Europe combined. By 2022, when the Ukrainians started requesting DPICMs, the DoD program to destroy its cluster munitions stockpile slowed to a crawl.

Despite US government assurances, the Ukrainians have likely received hundreds of thousands of ancient DPICM shells – shells which had a dud rate of 30% when new, and are now decades old. Accordingly, the number of Ukrainian civilians killed by cluster munitions has increased each year since the transfer.

On the battlefield, the huge influx of shells bought the Ukrainians valuable time, and allowed them to use artillery barrels far beyond their service life. But contrary to laudatory statements from the advocates of cluster munitions, the warhead type comes with tradeoffs. Due to the proliferation of drones, the front lines have become increasingly sparse. Isolated fireteams sit hundreds of yards apart, hidden in deep trenches to escape enemy ISR. Assaults are conducted with lightning speed on buggies and dirt bikes. In this environment, the promise of cluster warheads killing dozens of tightly packed troops is unrealistic. Cluster munitions are far less effective against deep fortifications, and even against infantry their tiny bomblets have to land in close proximity to a target to be lethal.

Even the tranche of United States-supplied cluster munitions, controversial because they harm civilians long after a war’s end, has lost some of its potency on the battlefield.

“Initially in September, we could hit large groups, but now they assault in much smaller units,” said the platoon commander, who was fighting outside Bakhmut. He added that the Russians have made their trenches even deeper and harder to hit. (NYT)

However many DPICMs the Pentagon sent, it wasn’t enough. Complaints of “shell hunger” continued after the transfer, with Ukrainian artillery teams saying they were lucky to fire two shells a day. And even if the new ammunition allowed barrels to be used longer, it didn’t solve the crippling barrel shortage the Ukrainians were suffering from – the sole US factory producing M777 barrels was unable to meet even a third of Ukrainian needs. A year after the Biden administration began transferring DPICM shells to Ukraine, a Reuters expose outlined the “dire” shell shortage Ukraine was suffering, but made no mention of the game-changing infusion of cluster shells. The hope that cluster munitions would break Russian trench lines in Zaporozhye in the summer of 2023 came to nothing, as the offensive failed to achieve a breakthrough. Czech initiatives to purchase and refurbish millions of old shells prevented disaster, but a worldwide TNT shortage put hard limits on how many new shells could be made, and the Pentagon failed to reach even half of its production goals in 2025. It’s currently procuring no more shells a month than it was a year ago. An explosion at a major Pentagon TNT supplier in October of this year likely pushed these goals back even further. Dan Rice was more optimistic – he claimed DPICMs alone had caused 425,000 Russian casualties in Ukraine, half of what he said Russia’s total casualties were, despite being a tiny minority of the warheads used in the war. Rice only succeeded in convincing one European state to withdraw from the CCM: Lithuania, which dropped out of the treaty in March 2025.

The DPICM didn’t change the game in Ukraine, even if it helped stave off defeat. Perhaps more important than the battlefield effects, though, is what it cost Ukraine’s allies, beyond dollars of aid and military equipment: their sense of moral superiority.

Eikenberry said the U.S. was losing its moral high ground by providing the weapons, which he said has been key to maintaining a cohesive international coalition backing Ukraine. “You’re starting to introduce chinks in the armor of the moral argument Ukrainians have in the situation.” (The Hill)

Game changer rating: 2/10

Next up. The tomahoax, to be followed by rotten tomatoes

I recall during the 2006 Israel-Hezbollah war how emergency stocks of ammunition was flown into Israel by US cargo planes ; and that Israeli specifically asked for the older version of MLRS cluster rockets as they proceeded to cover southern Lebanon grid by grid, per statement of Israeli artillery officer.